Who Were They Wednesday – Adolphe Saalfeld

Who Were They Wednesday Adolphe Saalfeld content: Elena Vukosa Adolphe Saalfeld was a German born chemist who moved to Britain in the 1880’s. He married in 1888 to Gertrude Harris. The couple would remain childless throughout their marriage. He was a self made business man and chairman of the chemists and distillers Sparks-White & Co. His main responsibility was overseeing the marketing of his line of concentrated perfumes and fragrances for distribution and sales. Saalfeld occupied cabin C-106 during the voyage to New York and was travelling with samples of his perfume products to open up a new outlet of floral fragrances in America. He was in the smoking room at the time of the collision and went back to his cabin. He left his perfume samples behind in his haste to leave the ship. During his account of the sinking he saw a few men and women go into a boat and promptly followed. He would later state that had they had enough boats there would’ve been time for saving every soul on board. Adolphe Saalfeld On his return to England he would be, like many other male survivors, ostracized for surviving the sinking of the Titanic. His family would report that he never slept properly again and often he would call on his chauffeur to drive him around the empty streets late in the night until he drifted off. Saalfeld died on June 5, 1926. His nephew Paul Danby would later be imprisoned in England throughout WWI for being an ethnic German. Paul and his family fled to the Netherlands but Paul, his wife, and elderly mother Clara would meet their deaths in concentration camps after the German invasion of that country as well. Paul’s two daughters would survive the holocaust. In 2000 Saalfeld’s satchel of oils was recovered in tact. The following video includes footage of Saalfeld’s satchel being recovered: https://youtu.be/rcWOUHHOAGk?t=329Sources: Photos: https://tamlynamberwanderlust.com/expo-review-titanic-artifact-exhibition-cape-town-part-1/adolphe-saalfelds-perfume/ Out of the 2004 Guernsey’s Catalogue, a very special piece: a first-class dinner menu from the dining saloon dated April 14, 1912. This particular menu was saved by first class Titanic survivor Adolphe Saalfeld. Mr. Saalfeld is said to have later given the menu to his accountant, whose family kept it for some time ‘until recently’ before the auction in 2004. This menu is one of three known examples of menus from the last meal, especially unique because, although it has the Café Parisien on the cover, the menu is actually for Titanic’s dining saloon. The menu sold at Christie’s in 1999, previously estimated to have sold for £8,000 to £12,000.

Wreck Thursday – The Bridge

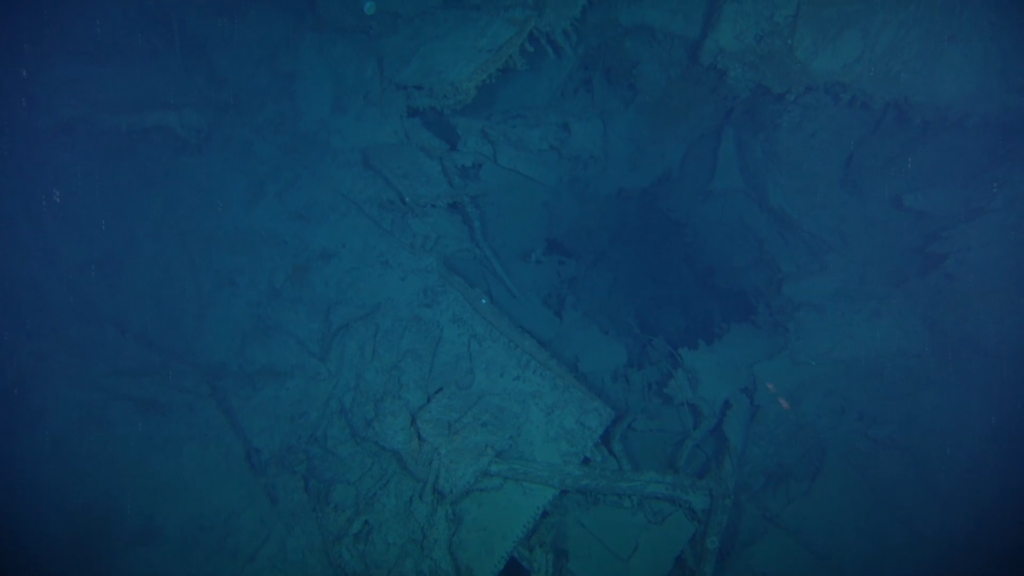

Wreck Thursday – The Bridge There are few more evocative locations on Titanic’s wreck than the remains of her Bridge. Watching the 1987 National Geographic documentary “Secrets of the Titanic,” filmed over 1985, 1986, and 1987, it is striking how Dr. Robert Ballard and those working with him believed that Titanic’s wreck would be far more intact. Ballard can be heard, while planning a dive, saying that he hoped to be able to “enter the Bridge” with his ROV Jason Jr. Of course, we now know that the Bridge is no longer an enclosed space as it was in 1912. While we can never be completely certain of exactly how the Bridge was destroyed during the bow section’s descent to the ocean floor, the pattern of the debris and the location of various parts of Bridge and its structural elements can give us some clues. t is likely that the foremast, which was swept backward and down as the ship plunged to the seabed, did some damage to the wooden roof and front of the Bridge, as well as potentially damaging the steel bulwark on which it now rests. Water rushing through the space may also have played some part in ripping away items inside. The real destructive force, however, appears to have been the downblast that resulted from the ship hitting the ocean floor with great force. This downward rush of water caused untold amounts of damage to the entire bow section, and it is likely that it completely destroyed the wooden structure of the Bridge, blasting it apart and downward. The debris of what was once the bridge tells at least some of the story of what happened to this space after it dipped below the surface. A mechanical linkage between the wheel on the Navigating Bridge and the telemotor in the Wheelhouse once ran along the ceiling of the Navigating Bridge. Today, it rests in a twisted mess on the floor of the Wheelhouse. Other structural elements are scattered on A-Deck below the Bridge. Had the rush of water swept the roof of the Bridge away, these items would be more likely found in the debris field somewhere astern of or away from the wreck itself. Instead, they lay close to where they were originally located. Today, there are two readily-recognizable features of the Bridge visible on the wreck. One is the low lip formed by the teak baseboard of the Wheelhouse, providing us an outline of that space and giving us our bearings. Directly aft of this lip is one of the most photographed and iconic spots on the wreck: the bronze telemotor that once connected the wheels on the Bridge to the massive steering gear located under the poop deck. It is the only item of equipment on the Bridge today that remains exactly where it was in 1912, marking the location from which Quartermaster Robert Hichens tried desperately to turn the Titanic away from the iceberg. As such, it has become the most popular spot for visitors to the wreck to place a plaque in memory of those lost and marking their visit. These rest in a row along the teak baseboard that once formed the front of the Wheelhouse. A closer inspection of the area of the Bridge and the space around it reveals much more. Check out the images to tour some of these smaller finds. One of the engine order telegraphs from the Navigating Bridge now rests on the port side of A deck, the drum separated slightly from the base. This proximity, much like that of the mechanical linkage noted earlier, indicates that the bridge was mostly destroyed by the downblast and not entirely by the falling mast or the rushing water. This is from 1996. The telegraph was recovered shortly after. A black cable, either for electricity or for the Wheelhouse telephones, runs along the forward teak baseboard of the Wheelhouse. This is from 2003. The bronze telemotor stands in the foreground, and some of the numerous plaques can be seen there as well. Directly to the left of the telemotor and in the center of the image is the mechanical linkage mentioned earlier. This is from 2003. In the background on the right, a wall of the Chartroom and Pilot’s Cabin, located behind the Wheelhouse, is visible. The collapsed bulwark of the port bridge wing can be seen in the background of this image, with the officer’s stairwell to the right and the cranked out davit for the port side emergency boat and Collapsible D to the left. This is from 1996. The collapsed rear wall of the starboard bridge wing now rests next to the cranked-in davit for the starboard emergency boat and Collapsible C. The davit was cranked in to connect Collapsible A and launch it after it was freed from the top of the Officer’s Quarters, but Titanic took her final plunge before this could be done and the boat was washed off the deck. This is from 1996. From 2003, this image shows the telemotor once again, but just behind it and resting diagonally across the Wheelhouse floor is a rigging line from the fallen foremast. Today, this is tangled with the linkage which connected the wheelhouse and navigation bridge helms. Also of interest is the base of the telemotor, including the various cables running from it into the deck. Also from 2003, this image shows the collapsed bulwark and forward wall of the wing cab on the starboard side. The remains of the raised platform that once ran along the base of the bulwark to allow an officer to step up and look over it can be seen here, as can the remains of the bulwark that connected with the aft wall of the wing cab (upper right of the image). The window for the forward wall of the wing cab is at the far left. In these views of the remains of the Bridge found on A deck, there are many

Who Were They Wednesday – Officer William McMaster Murdoch

Perhaps one of those most notable passengers in Titanic history is Father Browne, who didn’t make the entire crossing. He boarded the Titanic in first-class only to travel from Southampton to Queenstown.

Titanic Tours – The Bridge

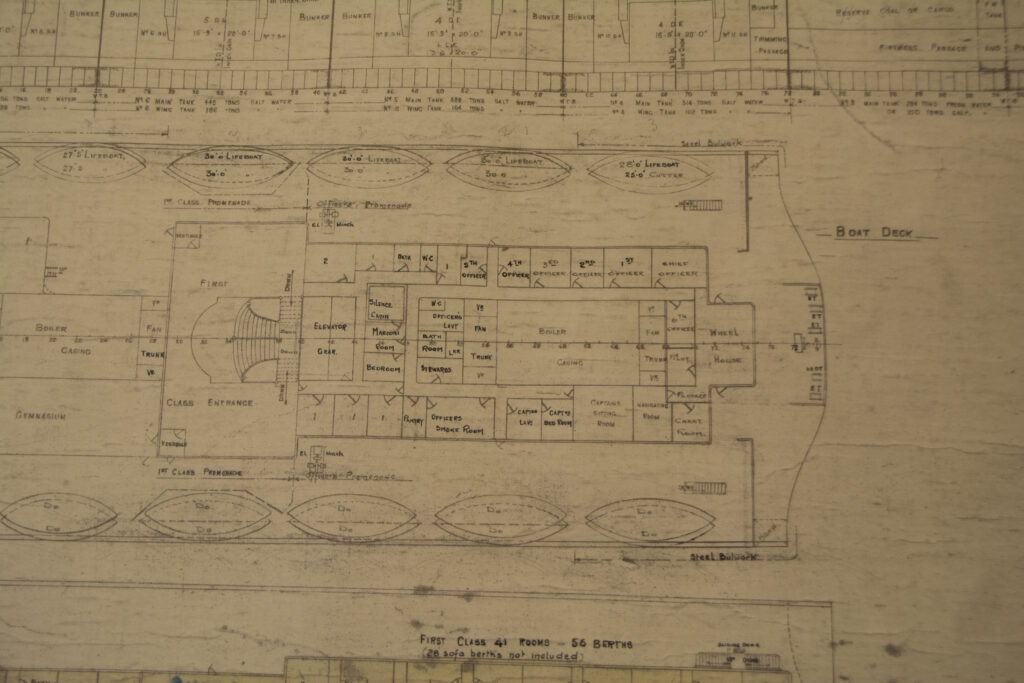

Titanic Tours – The Bridge A Titanic Connections Feature by Nicholas Dewitt The General Arrangement (GA) plans for the bridge area. These would be similar for both Olympic and Titanic, but Olympic was initially equipped with a curved-front Wheelhouse. Titanic’s was flat-fronted as presented here. The brain of any vessel at sea is her bridge. In the case of Titanic, the bridge is where some of the most consequential actions of 14 April 1912 occurred. This week, we’re heading there to take a look at this important space. Before we begin, a little historical note on the term “bridge.” Sailing vessels did not have a bridge, being instead navigated and commanded from the quarterdeck where the ship’s wheel could be found. But with the arrival of steam power and the equipping of ships with paddle boxes on their sides, the ship’s engineers needed a way to easily get from one paddle box to another and inspect the machinery. This took the form of a raised platform that stretched between the two boxes, forming a literal bridge. When paddles disappeared in favor of the screw propeller, the bridge stayed and became home to the ship’s command and navigating instruments. On the Olympic-class liners, as with other liners of the era, the bridge was located forward atop the superstructure. Denoted by a series of nine rectangular windows at the front center of the boat deck, the bridge encompassed a Navigating Bridge just behind the windows, an enclosed Wheelhouse situated behind that space, and encompassed the swept-back wings on either side that ended in a covered “cab” where officers could observe goings on below and to either side. We will explore all of these spaces in today’s tour. Connected to the Wheelhouse were a Chart Room, a Navigating Room, and quarters for a harbor pilot. We will explore these rooms at a later date. Navigating Bridge Each space above had a specific function to perform. Let’s begin with the Navigating Bridge. This space contained five order telegraphs, a wheel, and compass binnacle. There were also two small fold-down tables on either side wall that could be used for charts. While the wheel here was only manned when traveling near shore, the five telegraphs could and would be utilized to communicate with the various engine spaces throughout a voyage. The two outermost telegraphs were connected to the engine room to transmit orders for the speed of the ship. Each of the drums had an indicator for dead slow, slow, half astern, full astern, dead slow, slow, half ahead, full ahead, stop, stand by astern, and stand by ahead. The port handle of these telegraphs would transmit orders for the port engine and the starboard handle would do the same for the starboard engine. These two telegraphs were also connected to one another, so orders need only be “rung down” on one of the telegraphs. A third engine order telegraph was located directly to port of the wheel. This was the emergency telegraph. It had an independent connection to the engine room in case of the failure of the pair of main engine order telegraphs, but was otherwise the same in function. The two remaining telegraphs were for use when the ship was being docked or was near shore. These communicated with the Docking Bridge located on the poop. One was similar to the three engine order telegraphs, but would relay those commands to the Navigating Bridge from the Docking Bridge. The other had a dual set of commands on the side dials, one inner and one outer. Communicating both ways, the Navigating Bridge could send docking commands such as “Let Go Tug” or “Slack Away Stbd.” The Docking Bridge could also indicate information like “All Clear Stbd” or “Not Clear Stbd” to the Navigating Bridge. At the center of the Navigating Bridge stood the wheel and compass binnacle. The teak binnacle contained a 10” Kelvin-White compass. This was one of four main compasses aboard the Olympic-class ships, with the others being located in the Wheelhouse, a midships Compass Platform, and on the Docking Bridge. The compass inside the binnacle would have been lighted for easy viewing at night. Behind the compass binnacle was the ship’s wheel, one of three that could be used to steer the ship. This wheel, made of teak and measuring 3’ 9” in diameter, was mounted on a 34” high brass pedestal. This wheel was manned only when the ship was close to shore, but was connected to the telemotor in the Wheelhouse, which then connected it to the steering gear under the poop. The Navigating Bridge was fronted by nine large windows, with one of the ship’s bells mounted outside and above the center window. Two more windows opened out from the sides of the space, in line with the main engine order telegraphs. The General Arrangement (GA) plans for the bridge area. These would be similar for both Olympic and Titanic, but Olympic was initially equipped with a curved-front Wheelhouse. Titanic’s was flat-fronted as presented here. BRIDGE WINGS Accessed from the open sides of the Navigating Bridge were the two bridge wings, each with a steel bulwark swept back toward an overhanging bridge wing cab with windows on three sides. This area would be used for observation by officers on watch, providing an unobstructed view forward, to either side, and, thanks to the cab extending slightly over the side, downward to the sea. Immediately outside of the Navigating Bridge, nestled in the space where the bulwark met with the walls of the bridge, a pillar stood for use in mounting a pelorus. Also known as a “dumb compass,” a pelorus was used at times to take bearings. The pillar allowed it to be mounted above the bulwark for this purpose. Also of use in navigating the ship were the wing cabs, each of which was equipped with the sidelights used in navigation (red to port and green to starboard). These were designed so that they could each be

Wreck Thursday – The Funnels

Wreck Thursday – The Funnels On Tuesday, we took a look at Titanic’s four majestic funnels, their design, and the way all four of them provided ventilation to various spaces throughout the ship, from the boiler rooms to the galleys and beyond. During the sinking, Titanic’s funnels collapsed, either sinking on their own or being pulled down by the wreck itself. The collapse of the first funnel, depicted in countless films, was a key moment in the ship’s final plunge. But what happened next? Titanic’s funnels, along with her masts and rigging, were among the items that originally concerned the team lead by Robert Ballard and Jean-Louis Michel when they decided to use the towed sled Argo to film the wreck once it was discovered in 1985. If Argo had been too close to the decks, it might collide with the ship’s funnels or get stuck in the rigging. Fortunately for the explorers, the funnels were nowhere to be found and the ship’s masts had both collapsed. The funnels, made of relatively thin metal, had not survived intact. Instead, the pressure of the ocean had flattened them down, and much of their metal had corroded into barely-recognizable forms. Due to the extensive mapping of the wreck and the debris field, however, what remains of the funnels, not to mention to tubing, whistles, and ladders that once adorned them, has been found, photographed, and, in some cases, recovered. Let’s now take a tour of the images to see what remains of these once-beautiful and iconic funnels. First, in a 2001 image, we see the remains of one of the steam pipes that had allowed for an emergency release of steam pressure. This would’ve been on the forward or aft part of one of the funnels. Perhaps more interesting, however, are the remains of one set of Titanic’s working whistles. A set of the ship’s whistles were recovered in 1993 by RMS Titanic Incorporated (RMSTI). We will discuss these in a future post. In the next image, from 2003, we can see the gaping hole where the first funnel once stood. The violence with which this funnel collapsed during the sinking is evident from the torn remains of the stack in the center of the image, as well as the twisted piping near the bottom of the image. Hauntingly in the third image, also from 2003, we can see one of the escape ladders inside the uptake for the first funnel. Available as a pathway for personnel from the ship’s boiler rooms to escape to the upper decks in an emergency, we’re left to wonder if this ladder provided salvation for any of the few who escaped the ship’s lowest decks. In the fourth image, again from 2003, we can see a close-up of the twisted and broken steam pipe from the second image. This is even more evidence of the way in which the first funnel fell into the sea. In the fifth and sixth images, we’re still looking at the area around the first funnel, this time at the space just in front of it. The grate in the foreground covers the Fidley trunk. This open space forward of the stack would’ve provided ventilation to the boiler room below, as well as having space for the escape ladders we mentioned earlier. In the seventh image, we’ve moved aft to the crumbled remains of the base of the second funnel. Here, we get some idea of the subdivision within the funnel itself that was mentioned on Tuesday. Other, smaller pieces of the funnels have been found in the debris field around the wreck, including flattened remains of the funnels themselves and much of the piping that was once visible on the aft side of the third funnel. As new images come to light and are analyzed, we will hopefully be able to continue to piece together the final journey and status of what were once the ship’s most recognizable external feature. Content: Nick DewittImages: 2001 Telegraph2003 NOAA2010 NOAA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l0v1d1kZxqE The footage above was released from the 2022 dive (Oceangate) by CBS in November of 2022.

Who Were They Wednesday – Joseph George Scarrott

Perhaps one of those most notable passengers in Titanic history is Father Browne, who didn’t make the entire crossing. He boarded the Titanic in first-class only to travel from Southampton to Queenstown.

Who Were They Wednesday – Father Browne

Perhaps one of those most notable passengers in Titanic history is Father Browne, who didn’t make the entire crossing. He boarded the Titanic in first-class only to travel from Southampton to Queenstown.

The Voice of Sheila Macbeth Mitchell

THE VOICE OF SHEILA MACBETH MITCHELL This exclusive voice recording of Sheila Macbeth Mitchell was brought to you exclusively by Titanic Connections thanks to the Imperial War Museum (IWM). This audio is not for reproduction and may not be reposted anywhere.

Design D: The Interior

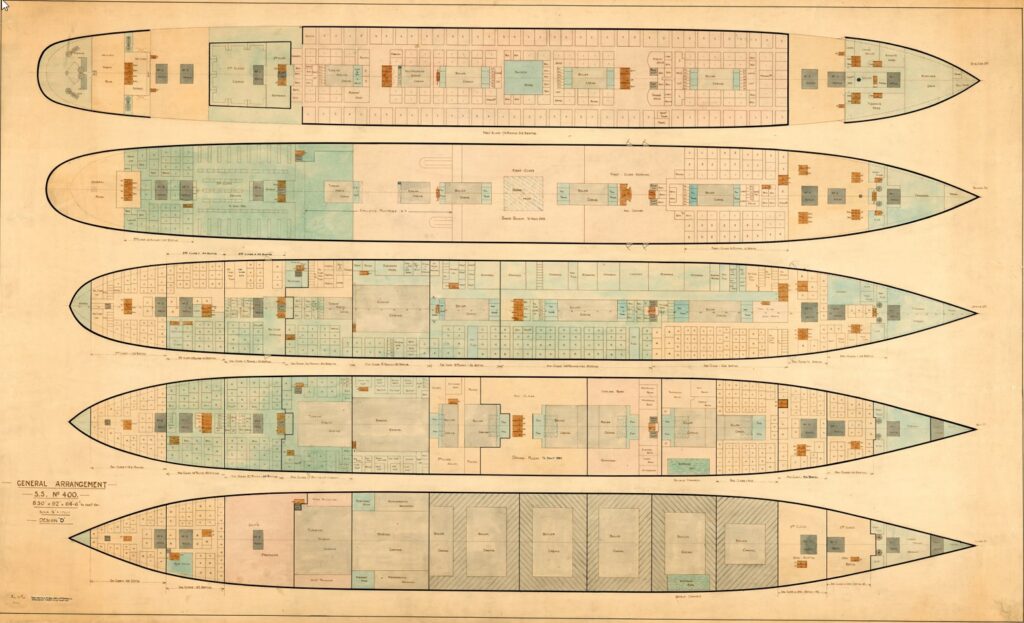

Titanic Design D: The Interior Did You Know… …that the interior arrangements in the original design for the Olympic-class ships, known as Design D, are just as varied from what was actually built as the external features we discussed in last week’s post? While the lack of a second mast after and a clustering of the ship’s lifeboats along the after boat deck is certainly a visual departure from the Olympic-class liners we’ve come to know and love, passengers stepping aboard would have found the ships to be very different from the ones that eventually set sail in 1911 and 1912. The most noticeable change would be the grand staircases. In both cases, these would have been more typical and rectangular staircases, similar to what we eventually saw in the Olympic-class’ second class spaces. The elevators, or lifts, would not have been located behind the forward grant staircase, but across from the front of the staircases, with a port and starboard elevator rather than a stand of three lifts. A deck would be very similar in layout to what was eventually built, with the Lounge, Smoking Room, Palm Court, and Reading and Writing Room all located in the same spots and with the same general shape. The aft part of the deck would have been smaller without the protrusion for the mast and also seems to be lacking the large cargo cranes, although it’s unclear if these are just omitted in the drawings, as no cranes appear around any hatches. B deck is very similar in design to the Olympic, with a large promenade space along the sides, but two major differences jump out from the drawing. The first is the lack of an A La Carte Restaurant for first class passengers. Instead, the second class smoking room is much enlarged. The more interesting change, however, comes near amidships, where there is a large space noted to be for a dome over the first class Dining Saloon. Olympic and her sisters would have a single-deck space for first class to dine, a radical departure from the grand, multi-deck spaces on other large liners built in England, Germany, and France. Design D, at least in this respect, places the Olympic-class ships closer to their contemporaries. This space is also marked on the plans for C deck. In both cases, this unbuilt dome would have taken up space later used for cabins and other small rooms. C deck is otherwise a near-mirror for the as-built ships, with only minor changes to the number and shape of rooms. D deck, however, is radically changed. The first class entrance and a second lounge space, what was later termed the reception room, is much larger in the original plans. Ironically, the final reception room was considered to be a bit too small. The major change here is that the entrances are not walled off from the staircase landing, providing a more open space without altering the rest of the floor plan. Interestingly, the otherwise typical staircase fans out on D deck into a shape more recognizable to our eyes. It is interesting to ponder what Design D’s Dining Saloon would have looked like with a two-deck dome space in its center. The third class General Room is housed here near the stern, as opposed to opposite the Smoking Room for that class on C deck in the final design. E deck holds little more than a few minor alterations, but F deck provides yet another surprise. The Gymnasium, to eventually be found on the starboard side of the Boat Deck, is on the starboard side here instead. The Turkish Bath area is shifted to the port side, where spaces for stewards were eventually located. While this seems a jarring change to us now, this may have been a more practical one in 1912. Olympic and Titanic did not have spaces for changing attached to their Gymnasium. Passengers using the facility would’ve had to pass through public spaces to change, something that would’ve been odd for the times. Most ships that housed a gymnasium at the time had it in the same location as found in Design D. G Deck holds our final major surprises, with the omission of a Squash Court forward being among two notable changes. The other is the location of the ship’s Post Office. Unlike in the final design, where the Post Office was forward on G Deck, Design D places it on the starboard side, but far aft in an area eventually occupied by third class berths. This would certainly have changed some of the story on the night of 14 April 1912, when the mail clerks were among the first to report that their area of the ship was flooding fast. Design D, like most initial designs for any structure, shows a lot of similarities with the what was finally built several years later, but it also shows some interesting differences, some that would’ve advanced beyond typical designs of the time and some which would’ve been a step backward from what eventually became Olympic and Titanic. It is fascinating to look at these designs today and imagine just how different these ships could’ve been. Written By: Nick DeWitt Photo Credit: Titanic Connections Archive Previous Next

Wreck Thursday: An Overview of Titanic’s Stern

Titanic’s Stern Section: An Overview Located 1,970 feet (590m approx) due South of the Titanic’s bow, lay the mangled remains of the Titanic’s stern section. This area of the ship, the last part of the great vessel to vanish beneath the North Atlantic surface, was a honeycomb of compartments that included crew spaces, 2nd & 3rd class quarters, cargo storage, engineering areas, refrigeration, kitchens, as well as having several large areas for the ventilation of her engineering spaces as well. It is for this exact reason (its design) that the stern section lies so mangled on the seafloor today… These great open areas, many of them containing air pockets, were dramatically, and catastrophically blasted apart by pressure as the great liners sank to the ocean’s depths. The stern section has been covered occasionally in previous Wreck Thursday posts, but it is my hope to ‘Return’ to the Stern in the next series of posts and see if we can’t pick out any details that have otherwise gone unnoticed… Lets begin this ‘Return’ with an overview of the entire Stern Section… Post by: Matthew Smathers Information & Images Courtesy Of:Encyclopedia Titanica,Daniel Klistorner,NOAA,Vasilije Ristovic,Father Browne Collection,Roy Mengot,Titanic: The Ship Magnificent,Bruce Beveridge,Ken Marschall,Mark Draper,Cyril Codus,Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute,Rms Titanic Inc.Storied Treasures Collection,