Concept of the Olympic Class

Design

While this tale is likely to be at least somewhat doubtful, the story of the trio of liners that would define the White Star Line in the 20th century often begins with a dinner in Belgravia in July of 1907.

As the story goes, on a summer evening after dinner and coffee at Lord William Pirrie’s London home, J. Bruce Ismay and Pirrie, with both their wives present, had a discussion about building three gigantic liners which would be the most-luxurious and largest vessels afloat and larger than any moving object yet made by man. The story continues that the general design for what became the Olympic-class started with just a drawing on a napkin. Thus, it is told, the great trio that would meet with so much hardship was born.

True or not, the Olympic-class ships were conceived in 1907, with an agreement being signed in September of that year to build three new behemoths that would compete with Cunard’s new Lusitania and Mauretania for the North Atlantic passenger traffic. Unlike Cunard’s speedsters, however, White Star’s ships would go all-in on luxurious accommodations to pair with good, but not record-breaking, speed. Alexander Carlisle, the brother-in-law of Lord Pirrie, was charged with constructing the three monster ships.

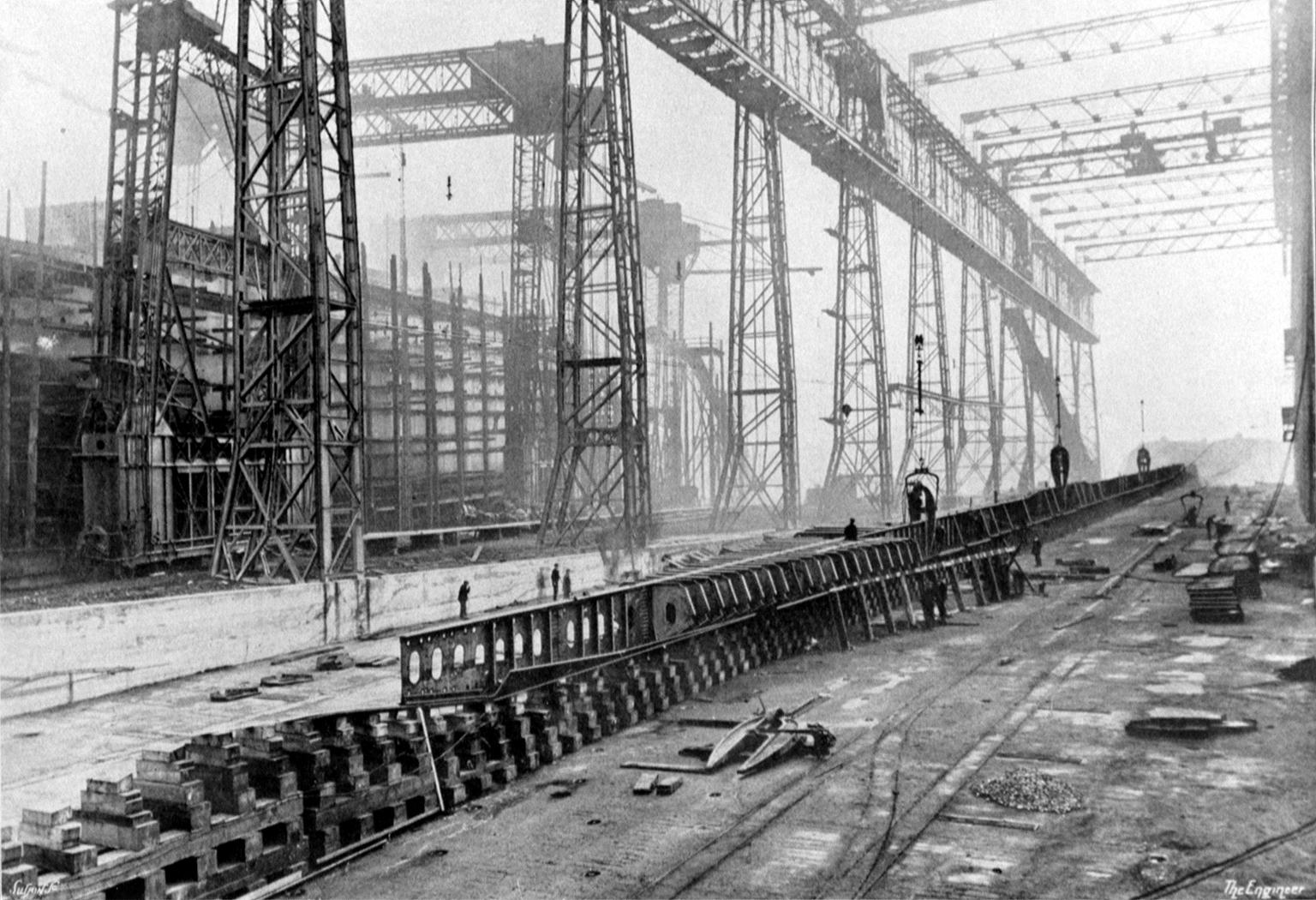

Rebuilding the Shipyard

Harland & Wolff had to demolish three existing slipways in order to construct two new and larger ones. Above them was erected the famous Arrol Gantry, with all matter of cranes and other ways of making the construction of a set of ships more manageable. In addition to new slipways and a towering gantry, Harland & Wolff had to create a new dry dock, the Thompson Graving Dock, to accommodate the ships when out of the water for maintenance and fitting out.

The dry dock was opened in 1911 and named after the chairman of the commissioner at the time, Robert Thompson. It has a length of 850 feet with caisson in inner position, but can be extended by an extra 37.5 feet. The dock holds 21 million gallons of water with the door in the inner position at 23 million in the outer, which at the time was the largest dry dock ever constructed. Harland & Wolff also constructed massive gantries that were built by Sir William Arrol & Co, which were 228ft (69 metres) high, 270ft (82m) wide and 840ft (260m) long.

Contract Signing

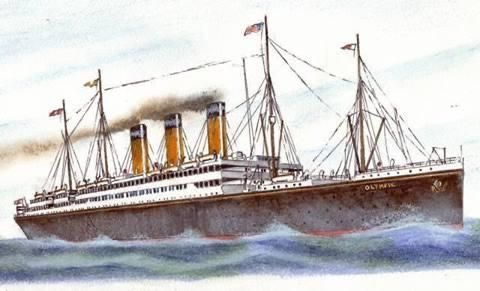

Ships need names, and on 22 April 1908, having already named yard number 400 ‘Olympic’ – a title previously intended for a never-built liner at the turn of the century – there was another Greek mythology-themed moniker for yard number 401.

She would be christened ‘Titanic’, and would come to represent that name in every conceivable fashion – from the size and strength intended, to the legend she eventually became.

On 31 July 1908, the contract letter was officially signed between the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company and Harland & Wolff. Work could now officially commence.

Pounding Of Rivets

Soon after, in December of 1908, Olympic’s keel was laid. Titanic’s keel would follow in the neighbouring slipway in March of 1909. Eventually, in November of 1911, the keel of the final ship, Britannic, would be laid where Olympic had once risen from her keel plates and into a grand ocean-going city. In slipway number one, next to the huge gantry, the tender SS Nomadic was also being built. Along with her near-sister Traffic, she would service the Olympic-class ships in their Cherbourg port calls. Nomadic would go on to have a storied career of her own, surviving to this day as the last of the ships of the White Star Line.

The first keel plates of Harland & Wolff yard number 401 are laid under the gargantuan Arrol Gantry in the Queens Island shipyard in slipway number three. Immediately next to this, in slipway number two, yard number 400 has already begun to rise, her keel plates having been laid the previous December. While yard number 400 would become the lauded “Old Reliable” RMS Olympic, the steel skeleton that now began to rise next to her would become the legendary RMS Titanic.

Titanic's stern is fabricated at the Darlington Forget Company in Durham and shipped to Belfast, where it arrived on 11 December at Harland and Wolff.

The stern framing for the Titanic is assembled, with the two pieces weighing in at 70 tons and having a total height of 68ft 3inches.

The Oceanic Steam Navigation Company Ltd puts in a special order for the chinaware that will grace the tables aboard the most luxurious liners ever built. Sticking to the company’s policy, the ships’ names are omitted from all of the tableware, which was manufactured by Stonier & Co.

Titanic’s steel hull plating is now all in place and riveted together.

Image: Titanic Connections Archive

An accident takes place when a crane on the gantry overhead collapses while lifting a large iron plate for the hull of the Titanic. Luckily, there was no damage caused to the vessel, and no injuries were reported.

An insurance coverage is agreed upon for both the Olympic and Titanic which is estimated at £750,000 for each ship with a £150,000 excess deductible rate.

The rudder for Titanic arrives at Harland & Wolff from Darlington aboard the Glenravel measuring a length of 78ft 8in, and a width of 15ft 3in.

The first anchor for Titanic arrives from Netherton, Worcestershire, weighing in at 15 tons.

Image: Titanic Connections Archive

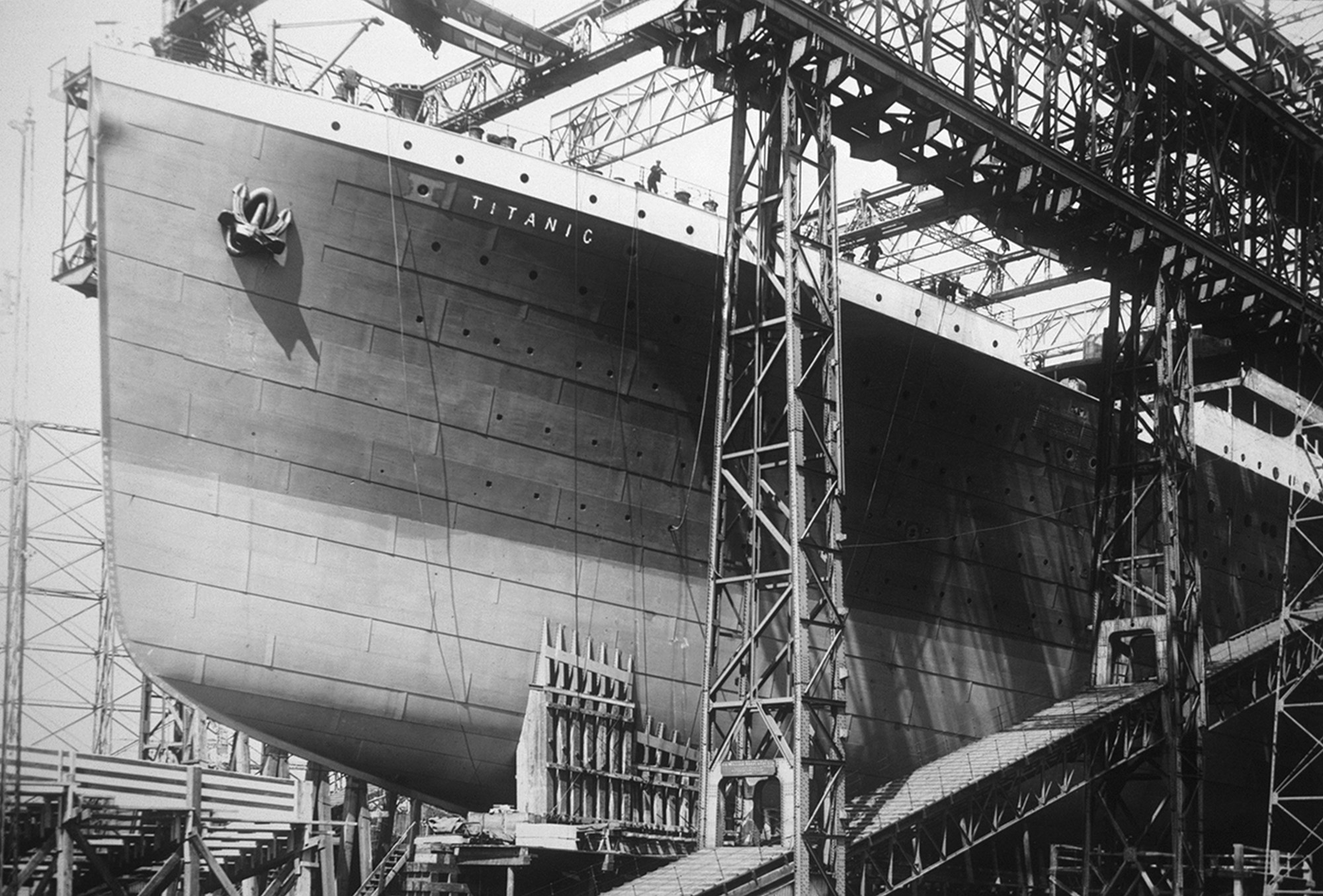

With over 100,000 shipyard workers, dignitaries, and interested citizens looking on from both the shipyard and the opposite banks of the River Lagan, Titanic is launched. She would not be christened, in accordance with White Star’s tradition. The report of a rocket signaled the moment she was to be released to the waters of the river. Twenty-two tons of tallow spread along the launching ways eased her journey, and several tons of drag chains brought the largest moving object yet made by man to a gentle stop in the river.

Image: Titanic Connections Archive

At 12:05pm, two rockets are fired as a warning to passing vessels, with a third following to indicate the start of the launch. A lever is depressed to release the launch triggers. Titanic hesitated for a moment and then, at 12:13pm, she moved for the first time and reached 12 knots as she slipped into the River Lagan with two piles of heavy drag chains, each weighing 80 tons, and six massive anchors attached to the hull to draw her to a standstill.

The whole event had taken 62 seconds, after which tugs took her in hand and towed her to the fitting-out basin nearby. She would stay there, with brief trips to the Thompson Graving Dock, until April of 1912, when she was finally ready for her sea trials.

The whole event had taken 62 seconds, after which tugs took her in hand and towed her to the fitting-out basin nearby. She would stay there, with brief trips to the Thompson Graving Dock, until April of 1912, when she was finally ready for her sea trials.

Following the maiden voyage of Olympic, White Star managing director J. Bruce Ismay and Harland & Wolff chief designer Thomas Andrews formulate a list of changes to Titanic that will both make her visually distinct from her sister ship, but will increase her gross tonnage and make her unquestionably the largest vessel afloat. Most noticeably, Titanic would not share the Olympic’s open A-deck and enclosed B-deck promenades. On B-Deck, the younger sister would have private promenades for her parlor suites and other expanded amenities. To make up for the lack of an enclosed promenade, the forward half of her A-deck promenade would be enclosed. Other changes, from cigar holders in the bathrooms and fewer screws in coat hooks to an enlarged Al a Carte Restaurant would help make the two ships distinct from one another.

Image: Titanic Connections Archive

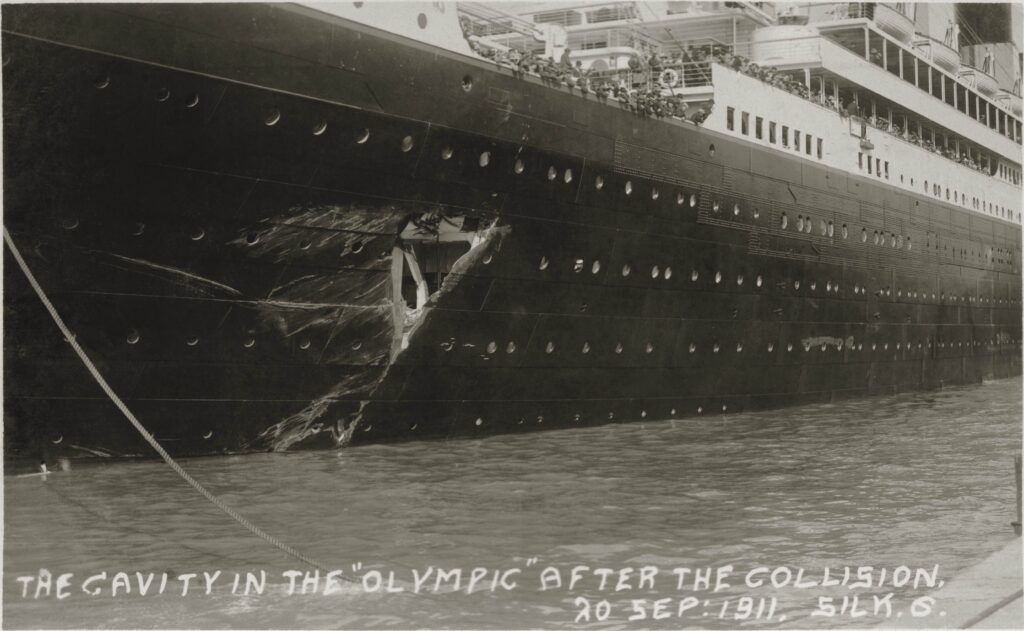

While on her fifth outbound crossing, Olympic collides with the British protected cruiser HMS Hawke in the Solent. The smaller cruiser was pulled inexplicably into the liner’s starboard quarter, puncturing her hull plates and damaging her starboard propeller shaft. The voyage cancelled, Olympic returns to Southampton for repairs that require Titanic to be largely put on hold and require the use of some parts intended for her. This delays Titanic’s planned mid-March maiden voyage.

The maiden voyage date for Titanic is set for 10 April 1912. Delayed from 20 March, the date would have originally marked the start of Titanic’s second round trip from Southampton.

William McMaster Murdoch, Chief Officer, Charles Herbert Lightoller, First Officer, and David Blair, Second Officer, report aboard their new assignment and begin to get acquainted with the White Star Line’s newest and finest liner. Lightoller would later note that it took him a fortnight to successfully find his way around the ship.

Herbert John Pitman, Third Officer, Joseph Groves Boxhall, Fourth Office, Harold Godfrey Lowe, Fifth Officer, and James Paul Moody, Sixth Officer reported aboard Titanic.

Edward John Smith, previously of the Olympic, officially takes command of the Titanic, relieving Herbert James Haddock, who had briefly commanded the vessel as her construction finished and who would now replace Smith aboard the older sister.

Her fitting out completed except for some last minute painting and other minor work, Titanic begins her sea trials at 6am. 119 crew members are joined by British Board of Trade inspector Francis Carruthers, who was already quite familiar with both Olympic-class ships. Also aboard are representatives from her builders, Harland & Wolff, and her owners, the International Mercantile Marine (IMM), which had bought the White Star Line in 1902 and made it the jewel of a vast shipping conglomerate. After a full day of speed and maneuvering tests, the liner briefly returns to Belfast around 7pm. Her trials satisfactory, she sails an hour later for Southampton. Unfortunately, a planned traditional stop at her port of registry, Liverpool, is canceled due to a delay in her trials.