The Aftermath of the Sinking

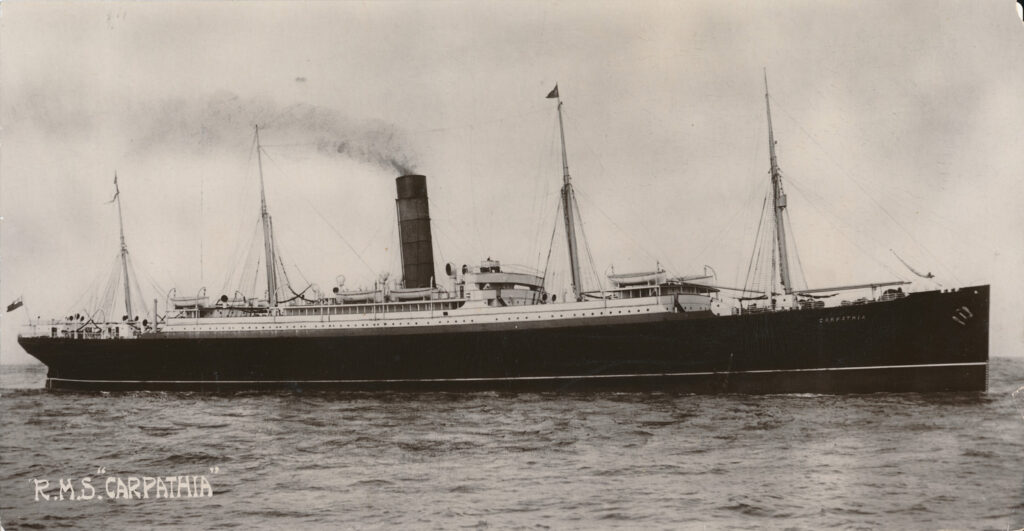

The RMS Carpathia had reached what for ships was middle age in 1912, having been in service since 1903.

On the night of 14-15 April, she was eastbound from New York, having sailed on 11 April with around 700 on board and bound for Fiume in the Mediterranean Sea. She was under the command of Captain Arthur H. Rostron, in command since January of that year.

When wireless operator Harold Cottam chanced upon the Titanic’s CQD while undoing his boots and preparing to turn in, he rushed the message to Rostron, who immediately swung the ship and her crew into action. Carpathia put on extra steam as she turned northwest and steered for Titanic’s reported position. As she went, her crew sped through a list of preparations Rostron had dictated on the spot that covered everything from steam in the winches for taking on cargo to which doctors would service which classes of survivors.

Reaching the first of Titanic’s lifeboats in around three and a half hours, Carpathia set about recovering 13 of Titanic’s boats and 712 survivors from the more than 2,200 that had been aboard. Having done all that could be done, Rostron turned his ship toward New York and delivered his sad and unexpected charges to their destination on 18 April.

Carpathia then returned to her routine of Mediterranean sailings until later serving in World War I as a troopship. Ironically, Carpathia herself would be lost to a torpedo in July of 1918.

The Recovery of the Victims

Once it became clear that not only had Titanic been lost, but also that nearly 1,500 passengers and crew had met their deaths in the icy North Atlantic, the White Star Line wasted little time in preparing to recover the bodies that now dotted the Atlantic waves. While none of the ships that rendezvoused with Carpathia at the site of the sinking found or recovered bodies, reports steadily came in of bodies, some singly and others in groups, floating in the shipping lanes.

Four ships, led by the cable ship Mackay-Bennett, set out from Halifax to locate and recover as many bodies as they could. Loaded with pine coffins, ice, and embalming supplies, these ships recovered 328 bodies. Five more would be recovered by other passing ships.

The recovery of the bodies led to the creation of the Barnstead Method, a detailed system for cataloging and identifying bodies and belongings and ensuring that they stayed together and were returned to the families of the lost.

While some victims were buried in family plots, 150 of those who perished were buried in Halifax where their graves are still tended and can be visited today.

While the main recovery operation took place immediately after the sinking, bodies turned up for over a month after Titanic sank. The last body recovered came in late May of 1912 when the sealer Algerine brought aboard the body of steward James McGrady, who was later buried in Halifax.

The Titanic Inquiries

Shock on both sides of the Atlantic over the worst maritime disaster to that point in history was immediate. That shock quickly gave way to a mixture of outrage and the need to understand how a ship that was lauded by trade publications as ‘practically unsinkable’ and that was considered the last word in maritime technology could have sunk on her maiden voyage after colliding at a glancing blow with an iceberg.

In the United States, Senator William Alden Smith of Michigan moved quickly to win approval for and piece together a full inquiry into the loss of the American-owned, British-flagged liner. Unwilling to allow their upstart cousins to have the last word, England also prepared to conduct its own investigation.

America, by virtue of the survivors landing there and Smith’s quick work, got the first crack, with the questioning opening in the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel on 19 April. It would run for 18 days and hear testimony from more than 80 witnesses. Their report was read in the Senate by Smith on

28 May 1912.

The British, waiting somewhat impatiently, would go second, opening their Wreck Commission on 2 May and carrying on until early July. The British enquiry, headed by Lord Mersey, would hear from around 100 witnesses, ask more than 25,000 questions, and publish their report on 30 July.

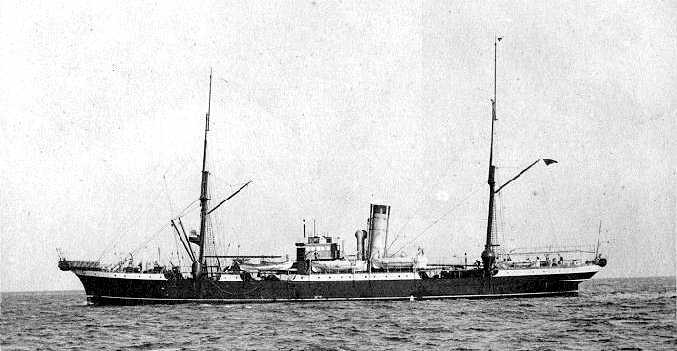

Both investigations arrived at similar conclusions. Both found fault with Captain Stanley Lord and his ship, the Californian, who would be created as the quintessential villains in the story. Both also managed to be respectful of Titanic’s dead captain, Edward J. Smith, finding that, while he showed ‘indifference to danger’ he had acted in ways consistent with the typical operation of steamers on the North Atlantic run up to that time.

Most significant of all, both investigations determined that this status quo which had led the able Smith to his death would now need to change.

Safer Shipping for All Passengers

Titanic’s lost exposed several dangerous practices and outdated regulations for steamships plying the North Atlantic. While the race to be fastest, largest, and most luxurious was far from over, that race would now be run according to some new rules.

First and most obviously, all ships would now carry enough lifeboats for every man, woman, and child aboard. While the idea that more boats on Titanic would’ve saved more lives has been proven somewhat dubious, the appalling loss of life could most easily be ascribed to outdated Board of Trade regulations dating to 1894, when the largest ships were barely a quarter of Titanic’s gross tonnage.

While lifeboats for all was the immediate rallying cry, other changes would prove far more valuable in practice.

In response to what has become known as the ‘California Incident’, all ships on the Atlantic would now be required to maintain a round-the-clock wireless watch. In addition to this, and also stemming from evidence of the Californian’s failure to come to the aid of Titanic, rockets at sea were now to be assumed to mean distress, regardless of coloration or any other considerations. No more would there need to be talk of ‘company signals’.

Most enduringly, the loss of Titanic led to the creation of the International Ice Patrol, led by the Revenue Cutter Service (later the US Coast Guard). This patrol, still active today, seeks out, reports, and, if needed, destroys dangerous icebergs.

Titanic’s loss also led to the first International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, or SOLAS as it’s now known. SOLAS not only created the ice patrol, it set safety standards for ships on the ocean. These standards are still enforced and modernized today.

A Timeline of the Aftermath

Between 15 and 45 minutes after entering water at around 28 degrees Fahrenheit, Titanic’s passengers and crew that were treading water, clinging to wreckage, or swimming for nearby boats slowly succumbed to the elements. Those without lifebelts would sink to the bottom after dying, while those in lifebelts floated on the swells. Slowly, an eerie silence fell over the scene.

Conversations took place in every boat about whether they should row back and try to pick up people in the water, but almost all of these conversations came to nothing as the fear of being swamped by panicked swimmers and the boats being overturned subdued those lucky enough to have left in a boat.

Eventually, Fifth Officer Lowe managed to corral four boats in addition to his boat 14 and effected a transfer of personnel so that he could take his boat back for a rescue attempt.

Lowe begins his rescue attempt, leaving the other four boats tied together. They would rescue four people from the water, with one, First Class Passenger William F. Hoyt, dying before the night was out.

Having arrived near the reported position of the Titanic, and after failing to hear from the stricken ship for some time, a green light was spotted nearby. This proved to be a flare held aloft by Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall in lifeboat two. Captain Rostron maneuvered the plucky Cunarder to allow the boats to arrive in her lee as the sea, so calm during the sinking, had begun to pick up.

Sometime later, Boxhall reports to the bridge and informs Rostron emotionally that the Titanic had gone down at 2:20am, just under two hours before.

The Leyland liner Californian, having been hove to since just after 11 the previous night, learns by wireless of the accident to the Titanic nearby and makes haste to the position reported. She will eventually arrive at Carpathia’s position and will be asked to search for bodies or survivors in the vicinity.

Charles Lightoller arrives alongside the Carpathia in lifeboat 12, having been rescued along with the others atop Collapsible B earlier in the night. Boat 12 is the last boat to arrive. By 8:35am, her passengers had been taken aboard along with 13 of the Titanic’s 20 boats. The others were set adrift.

Carpathia, with 712 survivors aboard, turns for New York to land the Titanic’s survivors.

J. Bruce Ismay, under the care of Carpathia’s physician, informs an inquiring Captain Haddock on Olympic, which had rushed at around 25 knots toward her sinking sister during the night but had been too far away to reach her, that he does not want the Titanic’s near twin to rendezvous with Carpathia to take on Titanic’s survivors. Ismay and others rightly felt that a second transfer at sea, not to mention the sight of a nearly-identical ship to the one where so many had lost loved ones less than 24 hours prior, would be a terrible idea. Olympic soon resumed her voyage to Southampton, assisting in transmitting information about the disaster with her powerful wireless apparatus.

The American cruiser Chester assumes escort duties alongside Carpathia, with her wireless eagerly asking for information regarding President William Howard Taft’s military aide Captain Archibald Butt, who had been aboard Titanic. Specific inquiries were ignored, by Carpathia operator Harold Cottam and surviving Titanic operator Harold Bride transmitted the names of survivors.

As Carpathia makes her way toward port, in Halifax, Nova Scotia, the cable ship Mackay-Bennett puts to see with 100 coffins, 100 long tons of ice, and various embalming supplies. She, along with other vessels, will be tasked with recovering the bodies of those lost.

Carpathia’s docking at Pier 54 in New York is completed. Having arrived earlier in the evening during a rainstorm, she first proceeded to Pier 59, where she lowered Titanic’s lifeboats into the empty berth the great liner would have occupied had she completed her voyage on schedule. With flashbulbs going off, she offloaded the 13 small boats and then proceeded back to Pier 54 for docking. Titanic’s survivors disembarked there into the care of friends, relatives, and relief organizations. The little liner then reprovisioned and took her passengers back to sea to complete her aborted voyage to the Mediterranean.

During this time, Senator William Alden Smith and Senator Francis G. Newlands boarded the liner and sought out J. Bruce Ismay to inform him that he and the surviving crew would be needed at an inquiry to begin almost immediately. Ismay, still weak, assented.

At the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City, Senator Smith convenes his inquiry into the loss of the Titanic. The inquiry would run until 25 May, with Smith and his assistants questioning 86 witnesses, examining Olympic, and producing more than 1,000 pages of transcripts.

While the inquiry was unfolding, the press began to vilify J. Bruce Ismay, painting him as cowardly and dastardly, twisting his efforts to return the surviving crew to their families in England (not to mention a Board of Trade investigation that he expected to happen soon after their return) into a scheme to escape justice, and turning him into a hated figure for many people on both sides of the ocean. While true the Ismay survived, his actions during the evacuation of the sinking liner border on heroic, if a bit panicked at times, and his survival alone appears to be the main charge against him.

The Mackay-Bennett arrives at the site of the disaster and begins her grim recovery work. Between this day and the 26th of April, when she departed for Halifax, the ship and her crew would recover 306 bodies, burying 116 of these at sea and carrying the remaining 190 back to Halifax.

The Mackay-Bennett arrives in Halifax, transferring her sad cargo to the ice rink of the Mayflower Curling Club. The crew would receive $100,000 for recovering the body of John Jacob Astor IV, using some of the money to pay for a headstone for an unknown small child that they had recovered and whose loss had touched them deeply. This child would be identified in 2007 as Third Class passengers Sidney Leslie Goodwin, who had perished at 19 months old.

Eventually 209 bodies would be brought ashore in Halifax and transported to the ice rink. 150 of these would never depart, and are interred in three cemeteries there.

The Wreck Commissioner’s Court hearings (the British Enquiry) open at the Scottish Drill Hall in Buckinghamgate, Westminster. This investigation would run until 3 July, hearing the testimony of almost 100 witnesses who answered more than 25,000 questions put to them by the various assessors, headed by Charles Bigham, Lord Mersey.

Saved from the Titanic, the first film adaptation of the disaster, premieres. Starring survivor Dorothy Gibson, the film by the Éclair Film Company garnered positive reviews. Unfortunately, the last known prints of the film were destroyed in a fire in March 1914.

Senator Smith presents the report of the inquiry’s findings to the United States Senate, with recommendations included to update safety regulations and shipboard practices.

The final report of the British Wreck Commissioner’s Court is published, also with recommendations included regarding the safety of passengers and crews on ships at sea.

The Radio Act of 1912, passed in mid-August, takes effect. It requires ships to maintain a 24-hour wireless watch and for ships to maintain contact with nearby vessels. It is a response to the situation in which the closest vessel to Titanic, the Californian, remained out of radio contact as her lone operator had gone to sleep.

The first International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) is passed, requiring lifeboats for all, echoing the Radio Act of 1912’s new wireless regulations, and mandating more rigorous safety procedures such as lifeboat drills for passengers. Due to World War I’s outbreak that year, the first convention didn’t come into effect right away. A new version would be adopted in 1929, with follow-on updates in 1948, 1960, 1974, and 1988. Smaller updates have occurred since the 1988 convention took effect, and SOLAS still governs the way vessels are built and operate at sea to this day.

SOLAS also formalized the mission of the International Ice Patrol, which had grown out of American naval and Coast Guard vessels patrolling the waters of the shipping lanes after the Titanic disaster. This organization still operates to this day, helping to keep the shipping lanes clear of ice, derelicts, and other obstructions that could cause a sinking similar to what happened on the frigid April night.

J. Bruce Ismay, perhaps the most notable survivor of the disaster, passes away in Mayfair, London, England. Ismay had been very private after the sinking and his rough handling at the hands of the press, but had remained engaged in maritime affairs for many years. At age 74, he suffered a stroke on 14 October, and he died three days later.

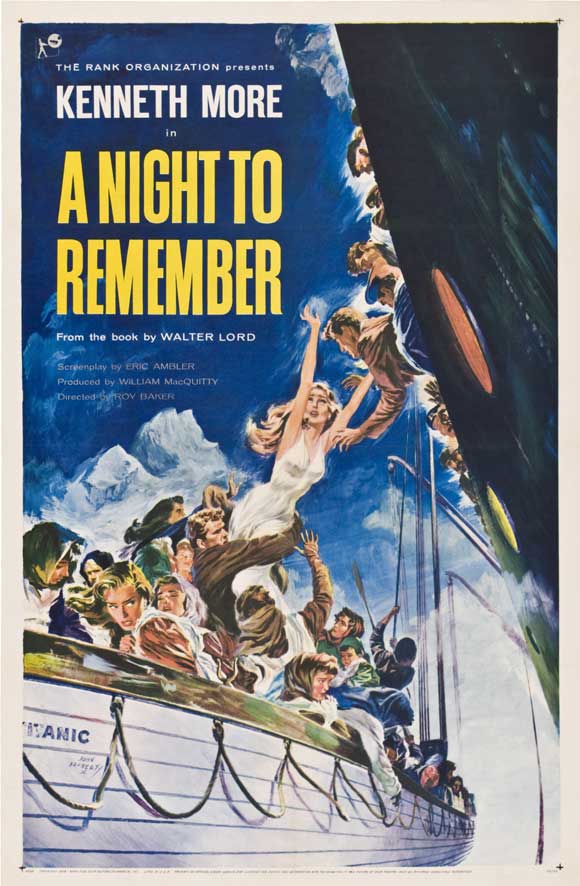

American historian Walter Lord publishes his book A Night to Remember about the sinking. While survivor accounts (led by those by Lawrence Beesley in 1912 and Archibald Grace in 1913) and analyses of the sinking (led by Filson Young’s book barely a month after the sinking) had existed for decades, Lord’s book will serve to reignite interest in the lost liner.

Starring Kenneth More and produced by William MacQuitty, who had witnessed Titanic’s launch in Belfast as a young boy, the film adaptation of Walter Lord’s book premieres in theaters. It proves a great success and, along with the book, continues to spur interest in the tragedy. Along with Fox’s 1953 Titanic, this film represents the beginning of the modern era in Titanic films. While a handful of depictions had been made between 1912’s Saved from the Titanic and the 1953 Hollywood film, including a Nazi propaganda adaptation in 1943, none remained easily viewable or popular in the post-World War II era.

Aged 84, Captain Stanley Lord, who had been master of the Californian the night the Titanic went to her grave, passed away. Having left Leyland soon after the inquiries and press vilified him as someone who could have helped prevent such a high death toll, Lord had remained at sea as a captain until 1927, retiring due to his health. After the film A Night to Remember portrayed him as sleeping warm in his bunk as the great liner sank nearby, his officers warning him of the odd sights across the water over and over, Lord sought to have his case reopened and his name cleared. Efforts were continued to this effect by Leslie Harrison of the Mercantile Marine Service Association, who vigorously represented Lord’s position at subsequent hearings, and Lord’s son. In 1992, the Marine Accident Investigation Branch issued a controversial report that both partially exonerated Lord and still castigated him for inaction. Lord’s actions remain a matter of spirited debate to this day.

The Titanic Historical Society is founded as the Titanic Enthusiasts of America by Edward S. Kamuda and five others. The group’s quarterly journal, the “Titanic Commutator,” has been published ever since and is one of several scholarly journals devoted to the ship and her history. The British Titanic Society would follow in 1987, with the Titanic International Society forming in 1989. Today, many countries have their own historical society devoted to the ship and several publish a regular journal.

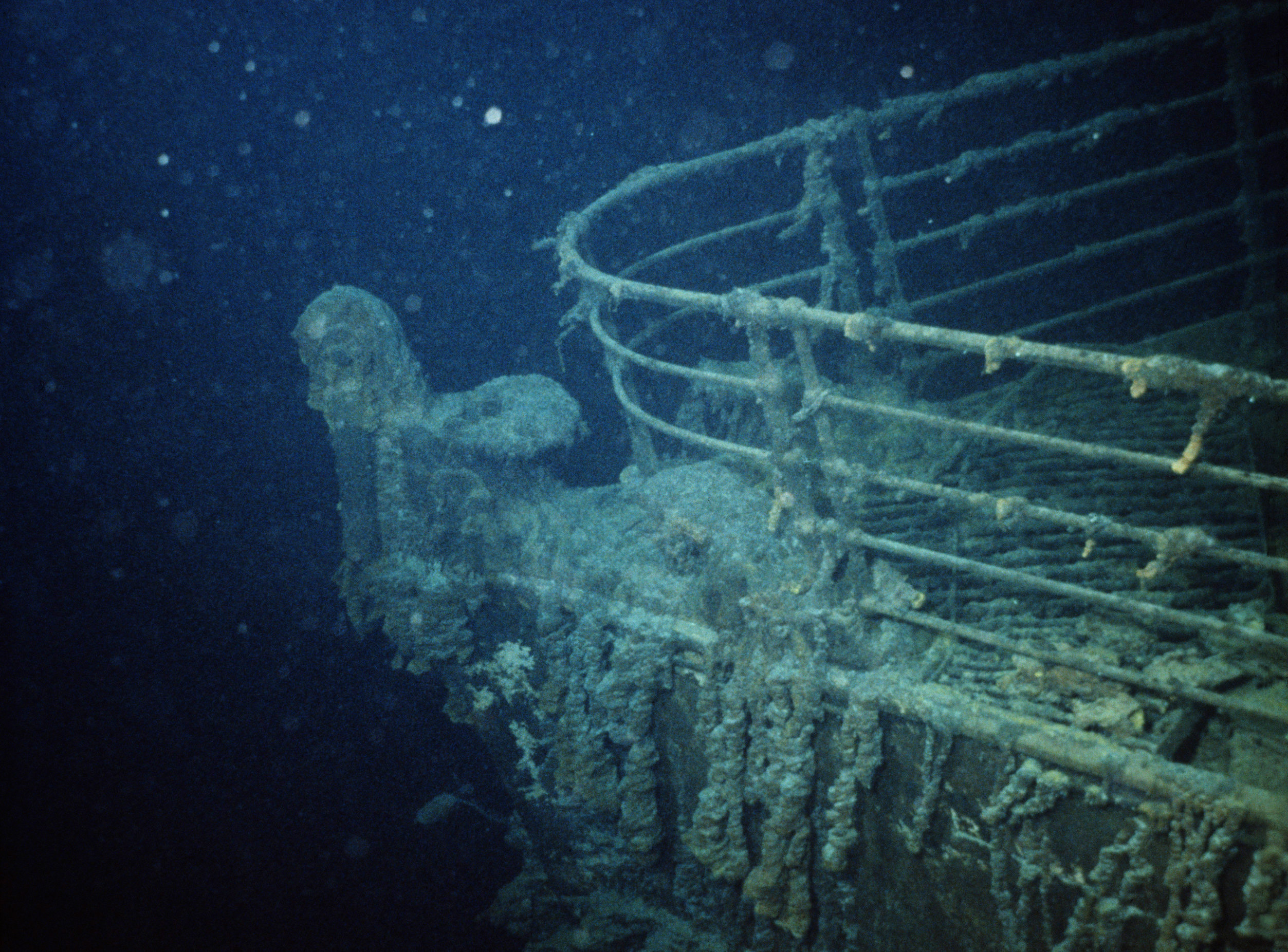

During one of the many expeditions mounted to find the wreck of the great liner during the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, debris, including a very recognizable boiler, appears on the video screens feeding from a towed camera sled back to the research vessel Knorr. Soon after, the bow section of the wreck was discovered, bringing an end to over 70 years of searching for the lost liner.

Dr. Robert Ballard and his team, using the deep sea submersible Alvin, become the first human visitors to the decks of Titanic since the night of her sinking in 1912. Using a remotely-operated vehicle (ROV) named Jason, Jr., Ballard explores the exterior and interior of the ship for the first time, confirming the previously-discredited testimony of several survivors who said the ship broke in two before sinking.

A first salvage expedition of 32 dives by the submarine Nautile is completed. Nearly 2,000 objects are brought to the surface, the first of many more over subsequent years. These are conserved and placed in museums and traveling exhibitions around the world. Dives are continued for both research and salvage purposes in many years afterwards, bringing back more artifacts and hours upon hours of film footage to go with thousands of photographs of the wreck. Scientific experiments are carried out to chart new life forms first discovered on the Titanic’s collapsing, deteriorating surfaces. This includes the “rusticles” which now give the ship a distinctive look

In Tokyo, Japan, a new blockbuster adaptation of the Titanic’s legendary story premieres. Directed by James Cameron, who completed his own dives to Titanic before filming and went on to make several other research trips afterward, the film becomes the highest-grossing of all-time, with a gross of nearly $2.2 billion including it’s 2012 and 2017 re-releases. It would eventually be surpassed by Avatar in 2010. As with A Night to Remember in 1955 (the book) and 1958 (the film) and the wreck’s discovery in 1985, Cameron’s film is responsible for another boom of Titanic interest, with new expeditions, products, and exhibitions, not to mention hundreds of new books, part of the response to the outpouring of enthusiasm for the lost ship and her story.

A section of Titanic’s hull, originally part of C and D decks, is lifted to the surface after failed attempts beginning in 1996. Dubbed the “Big Piece,” it has since been divided into a large and small section, the larger part on permanent display at the Luxor hotel and casino in Las Vegas, Nevada and the smaller piece, or “Little Big Piece,” exhibited in Orlando, Florida.

The last survivor of Titanic, 97 year old Millvina Dean, passes away in Ashurst, Hampshire in England. Born on 2 February 1912, Dean was the youngest passenger aboard and too young to remember the sinking, but she nevertheless became very active in Titanic circles in her later years, appearing at conventions, signing numerous autographs, and telling her story and that of her family in several documentaries. Her death saw Titanic pass from living memory.

While concerns about the ship collapsing due to deterioration and repeated salvage attempts have been voiced continuously, expeditions continue to reach Titanic every few years at most. While the interior of the wreck has thus far been spared by salvage efforts, due both to the complex nature of retrieving items from inside intricate and collapsing spaces and the stated desire of RMS Titanic Incorporated (RMSTI), the wreck’s owners, to stay away from those spaces for the time being, thousands of items have been retrieved from her debris field, ranging from the crow’s nest bell rung by Frederick Fleet to signal danger ahead to pieces of passenger luggage containing perfectly preserved paper items and clothing.

Titanic remains more popular than ever, with the 1997 blockbuster film being followed by further treatments on the big and small screen, a wealth of new scholarly and fiction treatments of the story in print, countless documentaries and websites, and many formal and informal groups such as Titanic Connections. Together, those historians, enthusiasts, artists, and others devoted to the ship, her history, and the stories of those who built and sailed aboard her, hope to keep her alive for future generations.