The Collison: 11:39 PM to 11:41 PM

High up in the crow’s nest, Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee are doubtlessly looking forward to being relieved for the 12am-2am watch, although their watch will be extended just over 20 minutes to account for the setback of the clocks at midnight by 47 minutes. This change is divided between the two watches as evenly as possible, with one watch extended by 23 minutes and the other by 24. Scanning the dark horizon where the stars merge into the sea, Fleet suddenly sees a shape looming directly ahead of the onrushing liner. Tugging immediately on the cord of the crow’s nest bell three times to indicate an object dead ahead, Fleet then reached for the phone connecting them to the ship’s bridge. Sixth Officer Moody answers the call after a moment, calmly asking the lookout what he has spotted. “Iceberg, dead ahead, sir,” or some slight variation of this, is shouted back to Moody by Fleet. It is likely that by the time Fleet and Moody’s brief conversation had concluded that First Office Murdoch had also seen the ice from the bridge wing and had begun swinging into action.

Steward Bishop"There's talk of an iceberg ma'am..."

Murdoch, Moody, and Quartermaster Robert Hichens take the following actions in quick succession to try and avoid a tremendously damaging collision with the iceberg staring them down:

- Rushing onto the bridge, Murdoch orders “Hard-a-starboard!” Under the tiller helm commands of the time, this would cause Hichens to turn the wheel counter-clockwise and the ship’s bow to swing slowly to port.

- At roughly the same time, Murdoch grasped the handles of the engine telegraphs and set them to “All Stop” for all of the ship’s engines. This is often incorrectly portrayed as Murdoch ordering the engines “Full Astern,” which would have been a jarring “crash stop” maneuver that would not have escaped the notice of all aboard.

- Moody observed Hichens as the latter man spun the wheel as fast as possible. Once the wheel hit against its stop, Moody reported to Murdoch that his order had been carried out and that the helm was hard over.

The three, along with the two lookouts in the crow’s nest, waited breathlessly to see if they’d acted in time. Titanic’s bow slowly, inexorably began to swing to port. Her stem cleared the side of the iceberg, which now began to pass along the ship’s starboard side. As stokers raced to shut dampers and engineers worked feverishly to close down the supply of steam to the liner’s engines, those watching far above must’ve felt like they’d narrowly missed the ice. Murdoch was well known as a cool shiphandler and had acted heroically in previous circumstances to save his ship from disaster.

This time, however, he was just a little too late. Chunks of ice broke from the iceberg and began cascading onto the forward well deck. A distant bumping and grinding noise transmitted itself to the men on the bridge, indicating that the ship was striking against the ice. His heart probably sinking, Murdoch rushed to the controls for the watertight doors and had them begin closing. He then ordered the helm “hard-a-port” in a fishtail maneuver to ensure that the giant liner’s stern would swing clear of the ice. As the berg passed the bridge, the grinding and bumping ceased and the ship and ice parted ways. The ice receded into the moonless night.

Below, Titanic was mortally wounded. Her forepeak, three cargo holds, and forwardmost boiler room were taking on water. Designed to float with her first four compartments open to the sea, Titanic had now exceeded that by one compartment.

The largest and safest ship afloat was going to sink.

The times represented in the sinking timeline are approximations based on triangulation and extrapolation from survivor accounts and other primary source evidence. While there is no way to be exact about what minute something occurred in most cases (with the notable exception of wireless transmissions that were logged by other vessels and by land stations), the sequence of events is accurate and the times given are a good approximation of how events unfolded over the period of time that the ship sank. What is presented here represents the best efforts of researchers and historians, including this author.

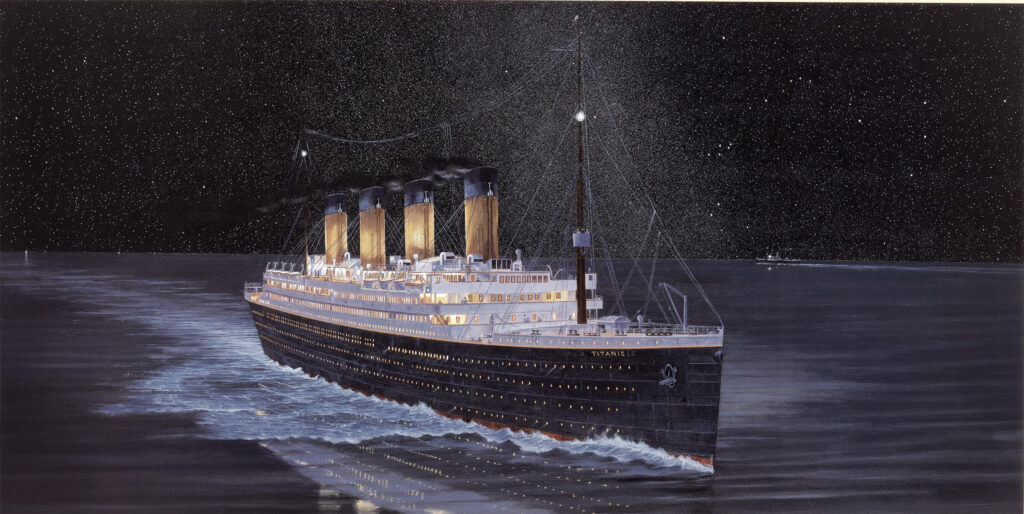

Artwork: Impact moment. RMS Titanic April 14, 1912 by Anton Logvynenko.

As Titanic glides to a stop, her bow now facing a little west of north, passengers become aware of the absence of the rhythmic thrum of her engines, part of their lives since they boarded. Captain Smith emerges on to the bridge to meet Fourth Officer Boxhall and First Officer Murdoch, inquiring as to what had happened. Murdoch explains that the ship has struck an iceberg and details his actions to avoid it. Boxhall is sent below immediately to check for damage. Also around this time, J. Bruce Ismay becomes aware that the ship is stopping and imagines that she may have thrown a propeller blade, an occurrence not uncommon for liners at sea and that Olympic had recently encountered on one of her voyages.

Captain Smith has the engine telegraphs rung down for “Slow Ahead” as he assesses the damage to and maneuverability of his vessel. He also sends Quartermaster Alfred Olliver to find Carpenter John Hutchinson and have him “sound” the ship. Boxhall, completing his abbreviated damage inspection and finding nothing, begins his trip back to the bridge to report.

Lamp Trimmer Samuel Hemming and Storekeeper Frank Prentice, investigating a mysterious hissing sound, discover air leaving the forepeak tank as it flooded. Reporting this to Chief Officer Henry Wilde, the two went to bed.

After perhaps 5 minutes, Captain Smith rings down on the engine telegraphs for “All Stop” once more, the ship having now tilted downward every so slightly and also having taken on a five-degree list toward her wounded starboard side. As the great liner comes to her final stop, Ismay arrives on the bridge asking what has happened. Informed by Smith that the ship appeared to be seriously damaged, Ismay returns toward his cabin and speaks to Chief Engineer Joseph Bell on the way. Bell is of the opinion that the damage is not serious enough to cause the liner to founder.

Having completed his inspection and arrived back on the bridge, Boxhall is sent below to find the carpenter, with Quartermaster Olliver having not yet returned from the same task. Around this same time, Thomas Andrews is observed rushing below, planning to inspect the damage himself.

Boxhall, having encountered Carpenter Hutchinson heading up to report to the captain that the ship was flooding quickly, arrives at the mail room after a postal clerk reports to him that the area is taking water fast. He finds water two feet below G deck and entering the ship at a high rate of speed. Andrews arrives a few minutes later on his own inspection.

Boxhall arrives on the bridge once again to make his report of the flooding in the mail room. Before leaving on his own damage inspection, Smith orders that the entire crew be called out and the lifeboats to be uncovered and readied for launching if needed.

Captain Smith, having arrived back from his damage inspection below, orders the boats to be swung out. He also gives orders to have the passengers don lifebelts and come on deck to the boats. Around this time, he also stops in the wireless room and informs Phillips and Bride that the ship has struck ice and that they should be prepared to send a distress call on his orders. By this time, steam was escaping from the pipes along the fore and aft side of the ship’s funnels, creating a deafening roar as it surged into the night. With the boilers no longer connected to the engines, the steam had to be vented to keep the steam pressure down. Also around this time, the ship’s band had gathered and begun to play various tunes to keep passengers calm.

Having just been spotted by passengers rushing up the ship’s forward grand staircase, Thomas Andrews arrives on the ship’s bridge to give his damage assessment. The news was grim. Andrews observed flooding in six compartments, two more than the ship was designed to survive losing. Five compartments were flooding from direct damage, with water being kept at bay for the time being in Boiler Room 5. With the damage in excess of the ship’s safety features, Andrews informed Smith and all present that Titanic would founder. Asked by Smith how long the ship had to live, Andrews calculated she had between 60 and 90 minutes left to her. Likely shaken by this pronouncement of doom, Smith headed to the wireless room to give orders that a call for assistance be sent.

The first CQD is sent by Jack Phillips, soon followed by a position that Smith had worked out shortly after the collision. CQ was understood as a call for all stations to stop transmitting and pay attention. D was code for distress or danger. While the new SOS call would also be sent on this night by Titanic, the new call was not yet in full use. “CQD CQD CQD CQD CQD CQD MGY” echoed into the night, with the distress signal followed by Titanic’s unique call letters. Cape Race, among others, heard the first call, and the small steamer Ypiranga heard another soon after.

As time continued to pass, passengers had begun to get the word that they were wanted on deck with lifebelts on, although exactly what was going on was still a mystery to many. In First Class, passengers gathered in the Lounge and Smoking Room and other public spaces, while in Third Class Steward John Hart helped steerage passengers with their lifebelts and began preparing to escort women and children to the boats. With First Officer Murdoch on the starboard side and Second Officer Lightoller on the port side, lifeboat preparations continued and the boats were provisioned, swung out, and lowered level with the deck for loading.

Provided with a new and “better” position by Fourth Officer Boxhall, Jack Phillips begins transmitting his distress calls once again with a position which would become famous, if inaccurate by some 13 miles: 41.46N, 50.14W.

Aboard the Cunard liner Carpathia, wireless operator Harold Cottam overhears Phillips’ call while unlacing his boots and preparing to switch off his set for the night, as Cyril Evans had done nearly an hour before aboard the Californian. Stunned by the gravity of the situation, Cottam signaled that he would tell his captain and rushed to the bridge, finding First Officer Horace Dean, but not the captain. Cottam then burst into Captain Arthur H. Rostron’s quarters and breathlessly explained to the surprised captain what he’d heard. Rostron swung into action immediately, having his eastbound ship turned around to steer northwest toward the position Cottam had provided. He also gave a series of orders to have his ship readied for a rescue at sea and set off for the position 58 miles away as fast as his ship could sail.

With lifeboat four temporarily useless, having been lowered to the level of A-deck where the windows of the enclosed promenade needed to be opened by a missing crank, Second Officer Lightoller begins work on the next boat aft, number six, and sends men below to open the gangway doors so that the boats can be loaded further down the hull to help prevent them from buckling fully-loaded high up at the boat deck. On the starboard side, First Officer Murdoch has loaded boat seven and begins lowering her as loading is completed for boat five and boat three. Lookout George Hogg commands this boat with roughly 28 people aboard.

Lifeboat five begins its journey down the falls toward the calm Atlantic. Third Officer Pitman is placed in command, becoming the first officer to leave the sinking liner. Approximately 36 people are in this boat as it goes down the falls. Disaster is narrowly averted when the ship tilts down at one end, the falls having been let go more quickly on one side than the other. At the same time, awaiting a long-overdue relief, Quartermaster George Rowe telephones the bridge after seeing a lifeboat drifting by on the starboard side. Perhaps incredulously, Fourth Officer Boxhall answers and informs Rowe that he and his relief, Quartermaster Arthur Bright, should report to the bridge immediately with the distress rockets stored under the poop deck. Arriving on the bridge shortly after, Rowe assists Boxhall

Boxhall sets off the first of eight socket signals to be launched into the night as loading of Boat three continues. Rowe and Bright will assist him with the rocket launches, which happen at short intervals in hopes of signaling a ship that has been sighted nearby, but that has not answered the wireless calls as yet.

Lifeboat three’s lowering begins, supervised by Murdoch and Fifth Officer Lowe. Seaman George Moore is placed in charge of this boat, containing around 32 people. Around this time, the steam blowing off from the pipes on each of the ship’s funnels finally ceases after more than an hour of deafening roaring.

In Boiler Room Five, Junior Assistant Second Engineer Jonathan Shepherd falls into a manhole opened to get access to some pumping systems. Shepherd breaks his leg and is carried to the pump room.

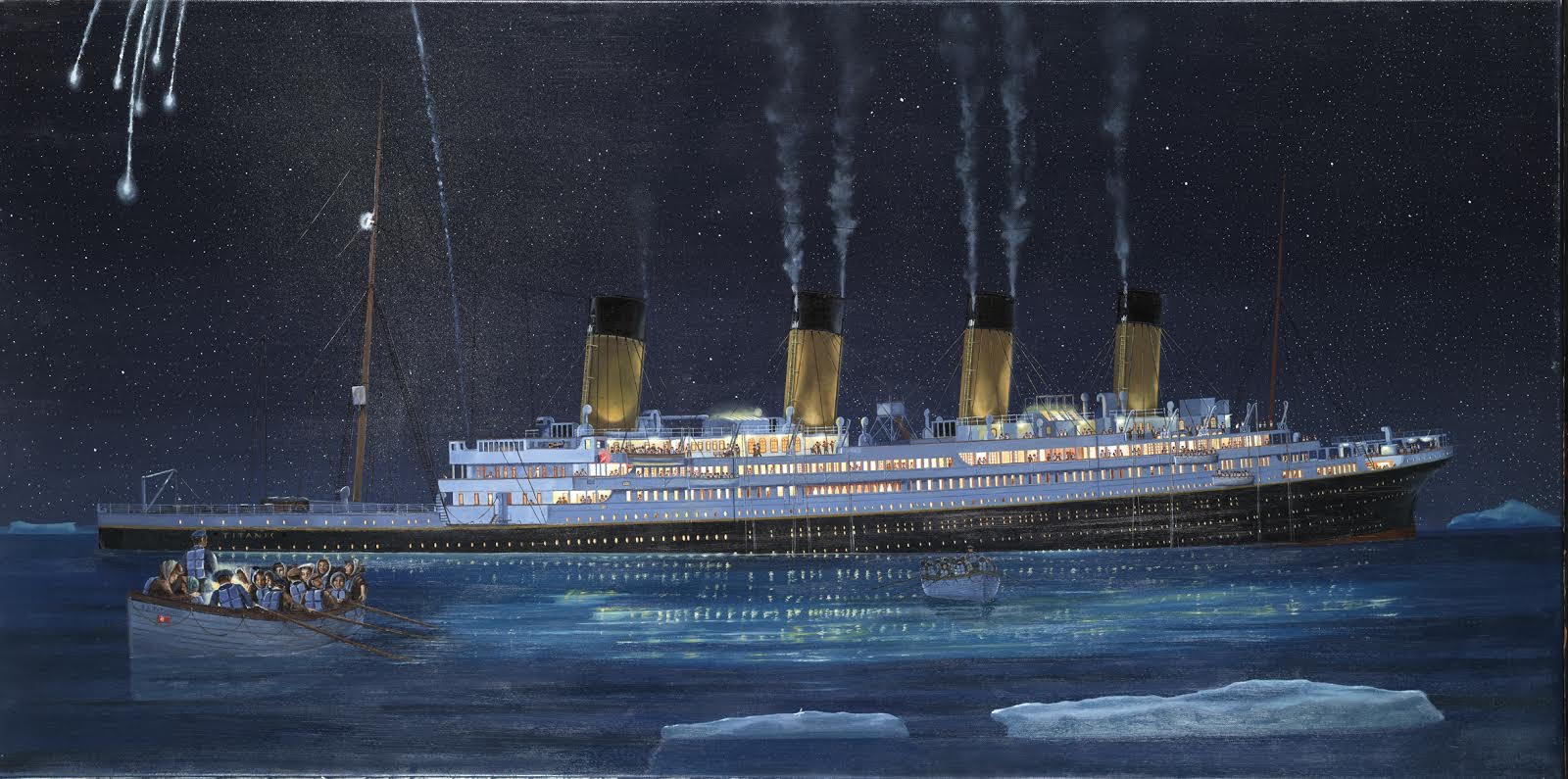

Artwork: by Simon Fisher

Lifeboat eight becomes the first boat on the port side to be launched, with Lightoller, Wilde, and Captain Smith supervising the process. Seaman Thomas Jones is put in command of a boat containing roughly 25 people. The port side boats’ launching had been delayed temporarily while Lightoller, Smith, Murdoch, and Wilde had repaired to Murdoch’s cabin where Lightoller retrieved a set of Webley revolvers and ammunition.

Lifeboat one, the starboard emergency cutter, is launched by Murdoch and Lowe. It contains only 12 people and is commanded by Lookout George Symons. Boat one has the lowest number of people of any boat launched with the davits. Among its passengers are Sir Cosmo and Lady Lucille Duff Gordon, who will later be wrongly accused of trying to bribe the boat’s crew to refrain from returning to the spot where the ship went down when Sir Cosmo evidently promised a “fiver” to each crewman who had lost all they owned and had their pay stopped at the moment the ship sank.

Lightoller, aware for the first time of the ship’s downward forward slope, supervises the launching of boat six, containing only one seaman among its 22 people as it left the deck: Quartermaster Robert Hichens, who was in charge. Canadian Major Arthur Peuchen, a yachtsman, volunteers to board the boat to assist with its navigation. Lightoller directs Peuchen to slide down the falls, which he successfully does. The boat also contains Margaret Brown, known to friends as Maggie, whose actions after the sinking will become famous.

As boat six is lowered, Leading Fireman Frederick Barrett witnesses a rush of water coming from between the boilers of Boiler Room Five. Barely escaping the suddenly-flooding room, Barrett makes his way topside.

Access Video One of the H&G Sinking Video with Exclusive Titanic Connections Sound Effects

Sixth Officer Moody sees to the lowering of boat 16, the first of the after eight boats to be lowered. One of the liner’s two Masters-at-Arms, Henry Joseph Bailey, will command this boat containing 52 people, the highest number yet aboard a boat when launched. With the ship noticeably down by the head and listing slightly, passengers were doubtless becoming more concerned and eager to leave the ship. Many, however, still seemed to believe that the disaster would be averted in time and that this “unsinkable” ship was only being evacuated as a precaution.

Around this time, Junior Second Engineer John Hesketh and presumably others pass the word to those working in the stokeholds that they are released from their duties and can leave.

Lowe is aboard boat 14 as it is lowered by Wilde and Lightoller. Around 40 people are aboard this boat when it reaches the water. During the lowering, Lowe was worried about passengers jumping into the boat and damaging or overturning it. He used his revolver to fire two shots along the hull to frighten passengers into staying away from his boat.

Boat 12 on the port side and nine on the starboard side are lowered. Boat 12 is under the command of Seaman John Poingdestre and has around 42 people aboard when launched. Boat nine, in charge of Boatswain’s Mate Albert Haines, has about 40 in it as it reaches the water.

Boat 11 is lowered by Murdoch with around 50 people in it. Seaman Sidney Humphreys was placed in command of this boat. This boat is able to avoid the water streaming from a discharge pump on the side of the hull which soon was to cause problems for another boat.

At practically the same time, Steward John Stewart spots Thomas Andrews standing in the Smoking Room studying Norman Wilkinson’s painting “Plymouth Harbor” hanging above the fireplace. Andrews did not respond to Stewart’s question as to whether he would try to survive the sinking. Andrews was later spotted leaving the sinking ship with Captain Smith, although Stewart’s sighting is often portrayed as Andrews’ final moments.

Artwork: by Simon Fisher

The Cape Race wireless station loses touch with the Titanic as her power begins to fade as the steam supplying her dynamos begins to ebb.

Boat 13 is launched by Murdoch and Moody. Leading Fireman Frederick Barrett took command of this boat, with roughly 55 people aboard it, including observant Second Class passenger Lawrence Beesley. Barrett would later be one of the key witnesses in the inquiries into the ship’s loss, while Beesley would go on to publish one of the first survivor accounts of the fateful voyage. As the boat reaches the water, but before she can let go the falls, a pump discharging water from the side of the ship pushes the boat backwards along the hull and under a descending boat 15. Barrett was able to cut away the falls with help at the last moment, and the boat was pushed clear of the oncoming lifeboat.

Boat 15 is also launched by the First and Sixth Officers. Fireman Frank Dymond was placed in charge of a boat with approximately 68 people aboard. Shouts from boat 13 below it provided just enough delay to this boat’s lowering to allow boat 13 to be freed from her falls and pushed clear before boat 15 came down directly on top of them.

Access Video Two of the H&G Sinking Video with Exclusive Titanic Connections Sound Effects

Boat two, with Fourth Officer Boxhall aboard and in command after having launched distress rockets from the bridge wing, is lowered by Wilde and Smith with 17 people in it. Captain Smith signals for the boat to approach the starboard gangway doors to take on more passengers. While Boxhall attempted to do this, he eventually gave up and rowed the boat away. It will become the first boat to reach the side of the Carpathia the next morning.

Murdoch launches boat 10 aft on the port side and Lightoller finally launches boat four forward on the same side. With Seaman Edward Buley in charge, boat 10 has 57 people aboard. Boat four, under the command of Quartermaster Walter Perkis, contains Madeleine Astor, the wife of Titanic’s richest passenger, John Jacob Astor IV. Astor inquires as to the number of the boat, and then sets off to allegedly free Titanic’s dogs from their kennels. In all, it is believed that this boat contained about 30 people. At this same time, Quartermaster Rowe fires the last of eight distress rockets.

Collapsible C is launched by Murdoch and Wilde from the same davits as boat 1, placing Quartermaster George Rowe in charge. As the boat, containing an estimated 43 people, begins to drop from the boat deck, J. Bruce Ismay steps aboard and takes a seat, having reportedly seen no other passengers who needed a place in the boat. Shaken by the sinking, Ismay had nevertheless worked diligently to assist during the evacuation, getting in the way of Lowe and Lightoller at various points. Ismay will be forever vilified for surviving the disaster that claimed the lives of 1,492 others, but there is nothing in the historical record to suggest that he did anything untoward beyond simply not dying.

Lightoller and Wilde launch Collapsible D from the same falls as boat 2. It will be the last boat to leave the ship via the davits, with Collapsibles A and B lashed on the roof of the officer’s quarters to either side of the forward funnel. This final boat launched is under the command of Quartermaster Arthur Bright and contains around 20 people.

Just before this boat is lowered, with Titanic’s list to port growing alarming, Wilde, Lightoller, and others shouted for people to move to the starboard side in an attempt to straight the ship up. While it is unconfirmed, it is believed that the ship’s remarkable stability during her sinking (most ships capsize before sinking) is due to her engineers and their staffs trimming her continually until they abandoned their spaces as they flooded. Given that the list, which had started out to starboard and then progressively shifted over to port, became noticeable enough to try to correct just after these areas were abandoned, it seems likely that trimming did occur.

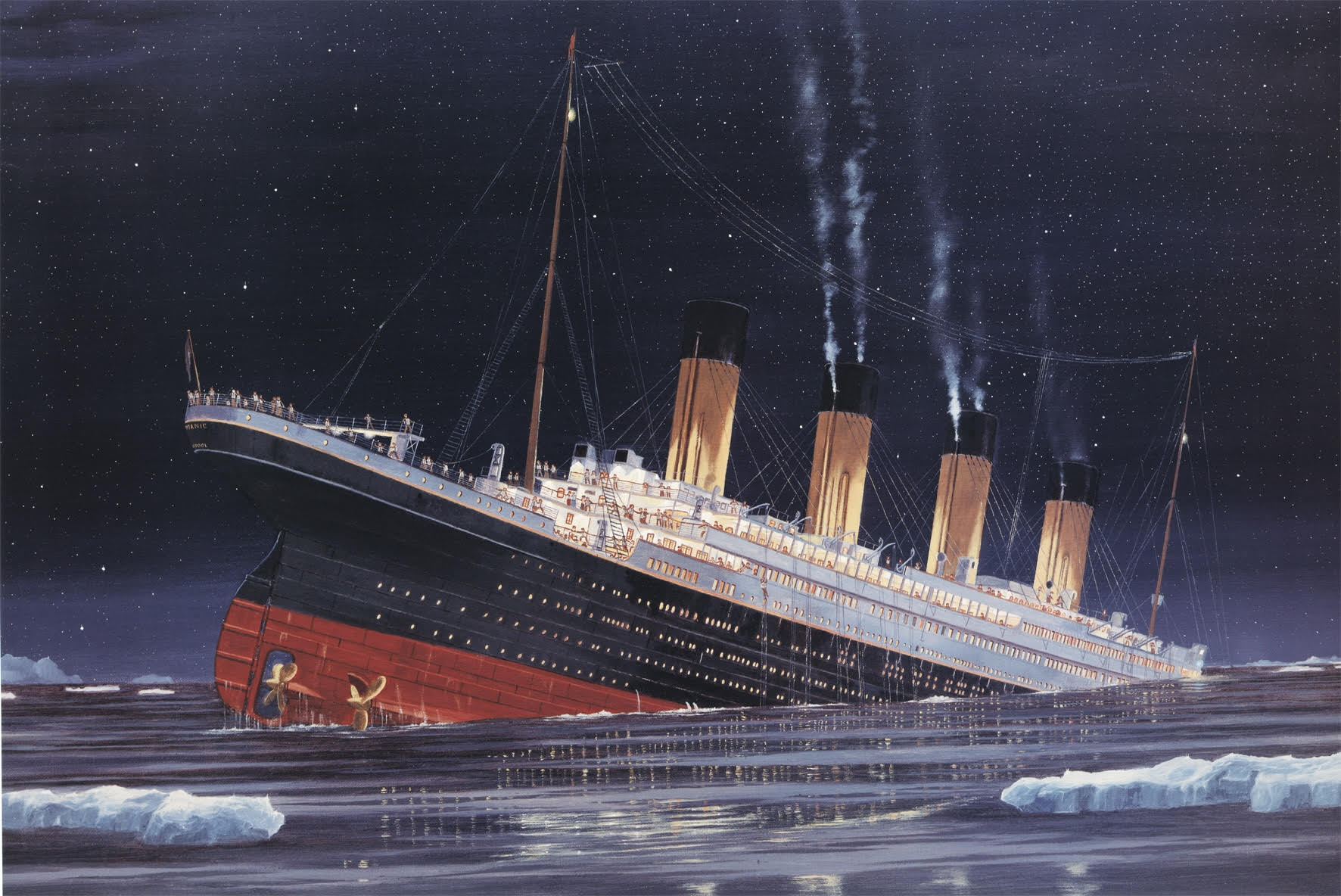

Artwork: Titanic The Final Plunge by Simon Fisher

The last wireless transmission from Titanic is sent: “CQD MGY.” It is picked up by the Allan liner Virginian, which noted that the signal was faint due to power loss on the sinking ship. After this, Phillips and Bride, having been released from duty by Captain Smith around 2am, finally abandoned the wireless room and attempted to leave the ship. Bride would make it to Collapsible B and survive, but Phillips, who may or may not have also made it briefly to that capsized boat, did not live.

Around this time, the Titanic’s heroic bandsmen, having played since before the evacuation had begun, played their final number. Much debate has arisen as to which song was played, with any of three settings of the hymn “Nearer My God to Thee,” the Episcopal hymn “Autumn,” and the popular waltz “Songe d’Automne” put forth at various times. Given Wallace Hartley’s reported intention to play “Nearer My God to Thee,” if ever confronted with this exact situation, it is likely he would have chosen this as his final piece on the sloping decks of Titanic. He likely either chose the Horbury or Propior Deo setting, both which were known to him. Ironically, the Bethany setting is the most frequently portrayed in film, despite this being a doubtful candidate.

Access Video Three of the H&G Sinking Video with Exclusive Titanic Connections Sound Effects

Titanic begins a quickening plunge downward, the bow and well deck submerging completely and water making its way aft at a fast pace. Collapsible A is washed off the deck as Murdoch and Moody attempt to attach it to the falls that had previously launched two other boats. Eventually 12 or 13 people would be pulled alive from this waterlogged boat. At the same time, on the other side of the forward funnel, Collapsible B is washed off the ship upside down. Second Officer Lightoller would eventually arrive on the upturned boat and take command of it and the nearly thirty people clinging to its keel. As these two boats are washed away from the ship, her bridge disappears beneath the surface of the Atlantic. It is reported that as the bridge disappeared, both Captain Smith and Thomas Andrews dove into the water from this area, although their final moments are in dispute.

Soon after this, as the plunge settled down momentarily, Lightoller, who had been washed from the deck along with Collapsible B, was pinned against the flooding intake for stokehold ventilation fans located ahead of the first funnel. A rush of hot air from below pushed him free as he was pulled under, allowing him to swim free from the sinking ship. After briefly trying for the crow’s nest nearby, Lightoller thought better of it and made for the upturned lifeboat where he would spend most of the night.

Moments later, the first funnel collapsed to one side with a crash as water reached its base. Some survivors reported people being sucked down into a funnel, likely either the hole left by the first or the second funnel. Water crashed into the glorious forward grand staircase around this time as well, likely breaking up the staircase’s elegant wood and wrought iron.

Access Video Four of the H&G Sinking Video with Exclusive Titanic Connections Sound Effects

After glowing steadily throughout the entire sinking, Titanic’s lights, which had slowly dimmed over the last several minutes, wink out. Except for a handful of dim emergency lights, darkness settles over the dying liner.

At about the same moment, a horrible rending, tearing, crashing sound is heard as the ship breaks into two pieces near the base of the third funnel. The liner’s final moments have arrived, with hundreds of passengers clinging to her after well deck and poop deck.

Artwork: by Simon Fisher

The stern of Titanic disappears below the surface of the Atlantic, leaving hundreds floating helplessly in the roiling water. Very little suction is reported, despite the fears of so many in the lifeboats standing as far off as possible. Within ten or twenty minutes, the two pieces of the ship would come to rest over two miles down, her bow striking stem-first and burying itself up to the anchors. The stern comes to rest around 2,000 feet away, with the fantail facing the bow.

Titanic will not be seen again by human eyes for over 70 years.