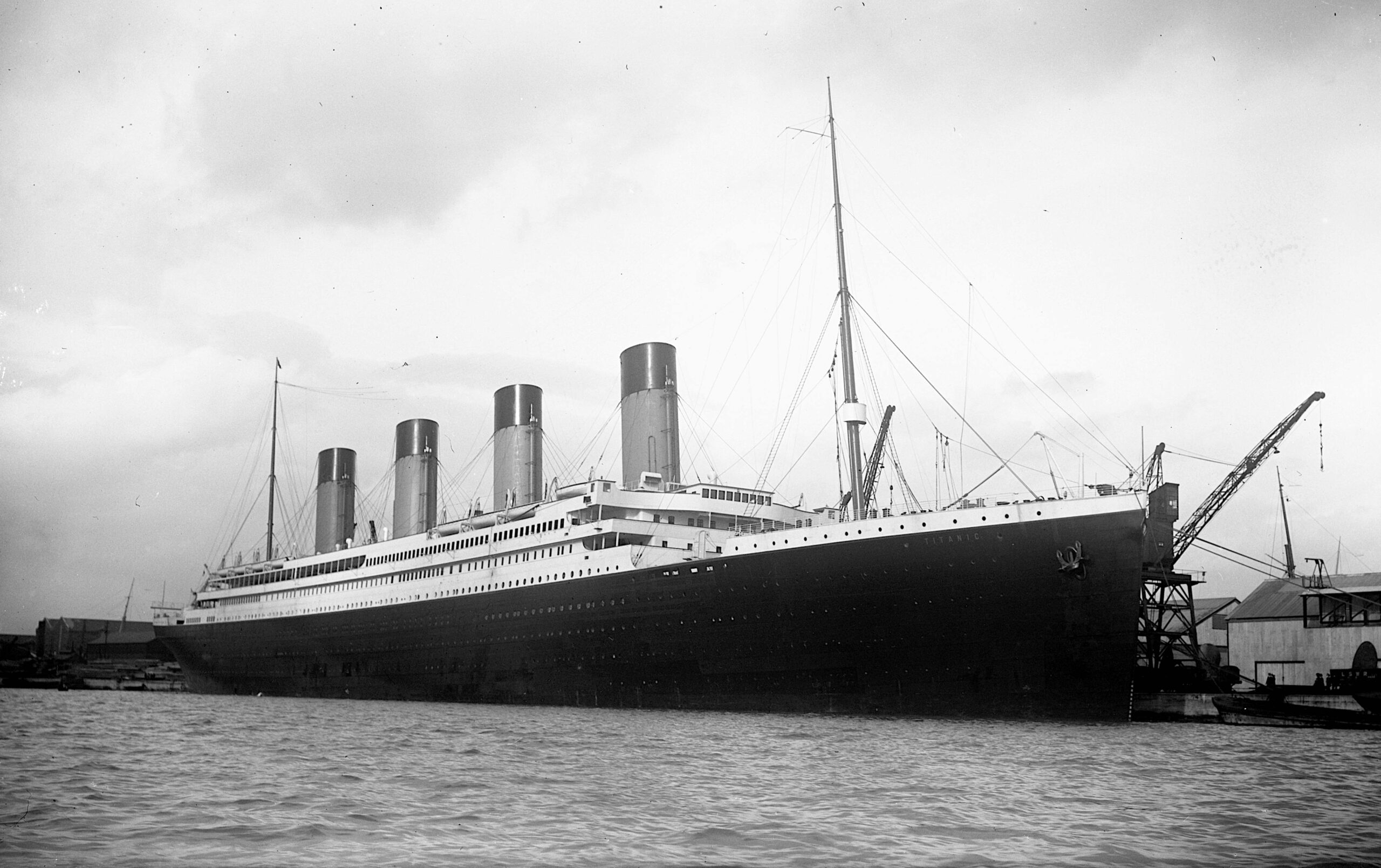

Titanic docks in Southampton at Berth 44 in the new Ocean Dock during the previous night between 11pm and 12am. Work now begins in earnest to prepare the great liner for her first crossing of the North Atlantic. The new ship would be docked stern-first, with her bow pointing toward the River Test, due to Southampton pilot George Bowyer and others’ experience with Olympic, which had proved difficult to extract from the dock stern-first due to the intricacies of the river.

Coaling of the great liner is completed. A coal strike meant that the docks were crowded with smaller IMM ships whose voyages were canceled to ensure that Titanic would sail both on-time and fully-coaled. The American Line’s Philadelphia and White Star’s Majestic shared the Ocean Dock with the new ship, and American’s New York and White Star’s Oceanic were moored ahead of the great ship along her path of departure down the Test. Titanic would take aboard over, 4,400 tons of coal in Southampton during this time, giving her nearly 5,900 tons for her voyage to New York. While not at full capacity, she was certainly not short of coal as would later be claimed.

The bulk of the new ship’s crew are signed on and brought aboard, setting to work immediately to prepare the liner for her first departure four days hence. Crates of china, cutlery, and glassware for all three classes were brought aboard and needed stowing, flowers needed to be arranged and distributed through the ship, and, as coaling was completed, the ship needed to be thoroughly cleaned to remove all traces of the ubiquitous coal dust which settled over ships as they were loaded with fuel.

Artwork: by Simon Fisher

After having been “dressed” in flags from stem to stern during her time in Southampton thus far, preparations for the voyage reach their finale. The flags are now stowed away. Paint is touched up on her four majestic funnels and other areas to ensure she looks her best when passengers arrive on the 10th.

Henry Tingle Wilde reports aboard as a late addition to the ship’s officers. Due to his familiarity with Olympic, where he’d previously been Captain Smith’s Chief Officer, Wilde was held back when Olympic departed on 3 April and would instead sail aboard Titanic as her Chief Officer. William Murdoch and Charles Lightoller were moved down to First and Second Officer, respectively, and David Blair, much to his chagrin, was put ashore to await a new assignment.

As Wilde officially assumes his duties as Chief Officer, Board of Trade Emigration Officer Maurice Clarke inspects the ship to ensure she meets the Board’s rigorous and detailed regulations. Clarke spent much time looking over the ship’s lifeboats, lifebelts, and other equipment before he cleared the ship to depart on the following day, much to the chagrin of her officers who presumably had many other tasks to accomplish that day.

Harland & Wolff Chief Designer Thomas Andrews steps up the gangplank and comes aboard, the first of many passengers to board the ship on that day. He is joined shortly by officers and crew who had been ashore overnight and now commenced with final preparations for the arrival of the ship’s first passengers later that morning. Around 7:30am, Captain Smith arrives on board and the blue ensign, denoting that Smith and a percentage of his officers and crew are Royal Naval reservists, is broken out at the stern. Flying the blue ensign instead of the red was considered an honor for any merchant vessel.

The crew is officially mustered in various parts of the ship. After inspection by Captain Smith, Maurice Clarke, and others, they were counted, roll taken, and a cursory medical inspection completed for each crew member.

The lifeboat drill required by the Board of Trade begins on the starboard boat deck. Officers Lowe and Moody take charge of boats 11 and 13, respectively, and the boats are uncovered, swung out, and lowered level with the liner’s boat deck. Eight crew enter each boat, lifebelts on, and the two boats are lowered into the waters of Ocean Dock. Rowed around the water briefly, the boats are then hoisted back aboard and re-covered. The entire drill lasts about 30 minutes. No one, of course, knows how important these and the ship’s other 18 boats will prove in just a few days’ time. Around the time the drill concludes, White Star managing director J. Bruce Ismay comes aboard the ship, no doubt excited for the company’s latest achievement to take to the sea in a few hours.

Boarding of passengers is now underway, with two special boat trains having arrived in Southampton with many of the ship’s passengers. Third Class passengers would first undergo medical examinations on the dock to ensure they were not bringing any kind of sickness aboard the great liner. The docks indeed bustle with activity. Cargoes are loaded aboard by the ship’s eight cranes and other booms, passengers stream through the various shell doors and begin the process of locating their cabins and finding their way around the new ship, and crew who had gone ashore after muster trickle back from pubs and last visits with loved ones. Visitors to the ship and her passengers also were aboard, briefly exploring the magnificent vessel that would soon depart.

Image: Titanic Connections Archive

The calls of “All ashore that’s going ashore” ring out and visitors and guests begin to depart. Smoke rises from the ship’s funnels as steam continues to be got up for the departure. Pilot George Bowyer and Captain Smith talk through the delicate procedure of taking such a large ship out of her berth, down the Test, down Southampton water, and into the open seas of the English Channel. Officers assume their departure stations at this time as well.

Having passed down Southampton water and then across the English Channel, Titanic drops anchor at Cherbourg, France. Passengers waiting since 4pm are now ferried out to the liner, which is anchored outside the harbor’s breakwater due to her large size. The White Star tender Traffic, followed by the Nomadic, tie up alongside the great hull of the mammoth new ship. Traffic carries 102 Third Class passengers along with mail for Queenstown and New York. She also takes off mail from Southampton for Europe. As the sun sets, Traffic departs and Nomadic journeys to the ship’s side. Nomadic carries 151 First and 28 Second Class passengers.

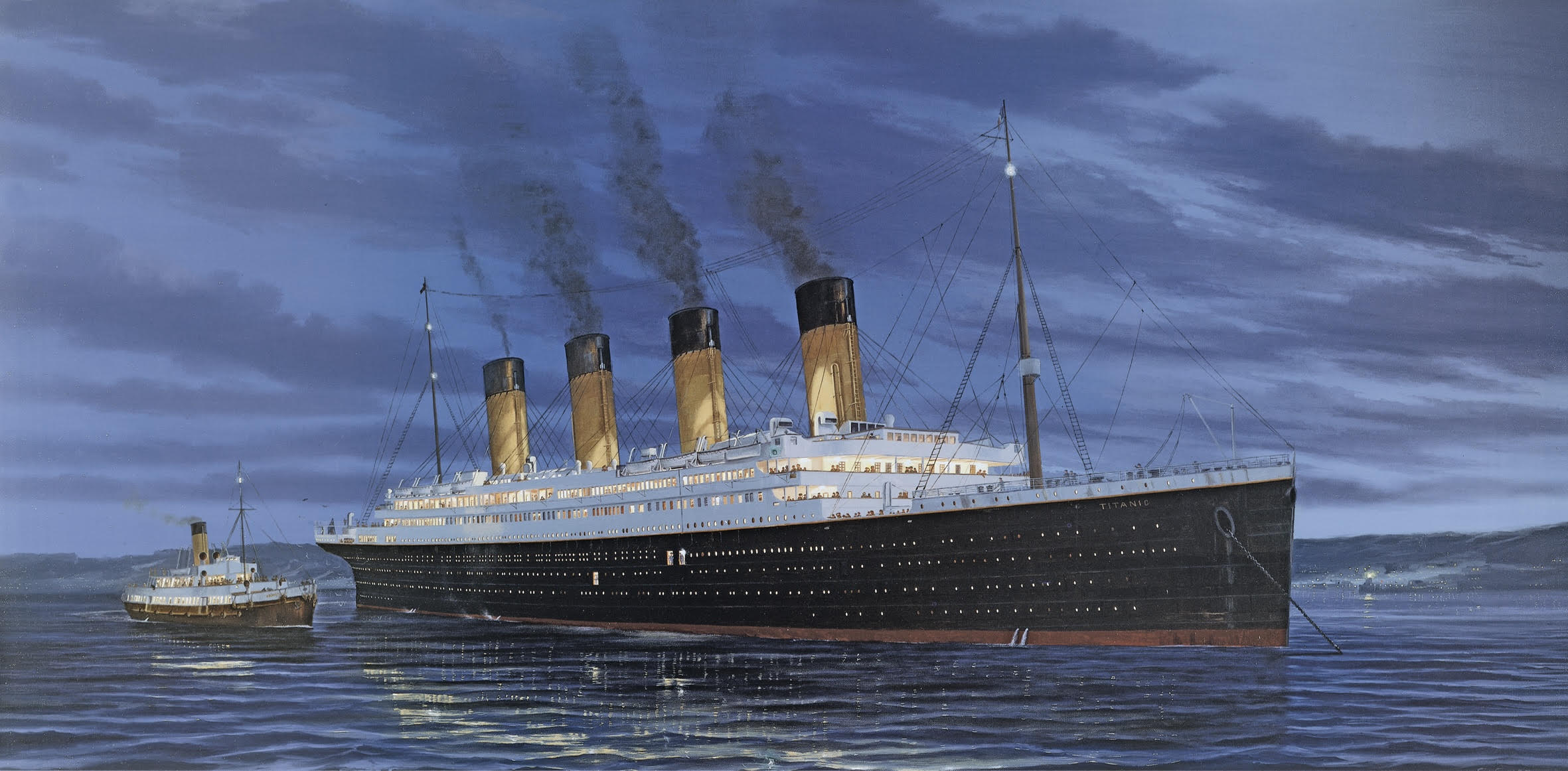

Artwork: Dusk, Cherbourg Harbour by Simon Fisher

Having taken aboard her passengers, cargo, and mails from Cherbourg, Titanic raises her anchor and begins to steam away from the port. She steams back into the English Channel for her short voyage to Queenstown, her final port of call, her speed rising to nearly 21 knots in hopes that she can make up some of the time after a delayed arrival in Cherbourg.

With the sun having risen and the ship steaming toward Queenstown, Titanic makes a series of serpentine S turns in order to adjust her compasses and properly calibrate them for the journey ahead.

Artwork: Voyage, First Morning by Elang Erlangga

Titanic’s run is calculated for the first day of her voyage. From her 2:20pm passing of Daunt’s Rock on the 11th to noon on the 12th, she is calculated to have run about 484 nautical miles.

Passengers routinely placed bets on the ship’s daily run, and there would doubtless have been great interest in this information when it was posted each afternoon. Officers’ knowledge was often solicited by passengers when possible and not- inconsiderable sums of money could be won in the daily pools.

After a speedy crossing of the Channel, Titanic drops anchor at Queenstown. As with Cherbourg, the liner is too large to enter the harbor proper. She anchors two miles from shore near Roches Point. In a repeat of her stop at Cherbourg, two small tenders, this time Ireland and America, steam out from the harbor to tie up alongside and disgorge their passengers, cargoes, and mails. America arrives first on her port side, with Ireland stopping on her starboard side. As the mails were exchanged once again, three First, seven Second, and 113 Third Class passengers come aboard. At the same time, vendors in “bum” boats come alongside and then aboard to sell laces and other wares. Seven passengers disembarked, among them Father Francis Browne, whose photographs are now among the only ones of the great ship in service.

With a bagpiper playing “Erin’s Lament,” Titanic raises her anchor and steams slowly away from her final port of call. On board at this time are 2,208 passengers and crew, thousands of sacks of mail, and many tons of cargo. The great liner passes down the Irish coast toward Daunt’s Rock, the official starting point of the Atlantic crossing, which she reaches in less than an hour as her engine revolutions continue to increase and she is opened up to full speed ahead.

The first of several warnings of ice along the Great Circle Route is received aboard Titanic by her wireless operators, John “Jack” Phillips and Harold Bride. This one, from the French Line’s La Touraine, noted a “tick icefield” at 44.58 N, 50.40 W and “another icefield and two icebergs” at 45.20 N, 45.09 W. Like most messages directed to the new liner, it also included congratulations and best wishes on the occasion of the ship’s maiden voyage. Titanic acknowledged the message, with a reply from Captain Smith being sent at 6:21pm.

As she steams through the North Atlantic, Titanic encounters some of the best weather of her voyage, with temperatures near 60 degrees and broken cloud cover overhead. At noon, the run for the ship’s first full day on the Atlantic crossing is calculated and posted. She has covered about 519 nautical miles since her position at noon on the 12th.

As passengers continue to enjoy the ship’s many amenities, and J. Bruce Ismay, Thomas Andrews, and the ship’s officers marvel at how well she is performing thus far on her maiden voyage, crewmen deep in the bowels of the ship finally extinguish a coal fire that had been burning since her Belfast departure. While much has been made of this fire by sensationalists and conspiracy theorists, coal bunker fires were a common feature of liners of the day and posed no threat to the ship’s safety. It also, through an exhaustive study published by Bill Wormstedt, Mark Chirnside, Tad Fitch, Samuel Halpern, J. Kent Layton, Ioannis Georgiou, and Steve Hall, has been proven to have had no adverse impact on the ship’s sinking.

Senior wireless operator Phillips begins having serious trouble transmitting with Titanic’s wireless set. After awakening his partner Bride, the two set about locating the trouble with an aim to fix it. This action, in violation of standing Marconi policy to operate on an emergency set until making port, will prove to be of immense value in just about 24 hours.

The trouble with the wireless system is finally solved, with Jack Phillips and Harold Bride binding the leads from a secondary transformer in rubber tape to prevent them from contact with other parts of the apparatus after they had burned through their casing. With the set back in action at full power, Phillips and Bride begin clearing a backlog of messages that had to await their hours of repair work.

The day dawns in a brilliant sunrise, Titanic’s last. Passengers continued to enjoy her many features. Colonel Archibald Gracie took a dip in her pool after a game of squash and then visited the ship’s gymnasium and instructor T.W. McCawley. Other passengers breakfasted as the morning wore on and then prepared for religious services in all three classes.

A new ice warning is received, this time from the Cunard liner Caronia. The two-funneled Cunarder warned of “bergs, growlers, and field ice” at 42N and from 49 to 51 W that had been reported by other ships traveling west. This message was acknowledged by Captain Smith at 10:28am. It would be the first of several documented ice warnings that day.

Captain Smith leads Sunday services in First Class in the dining saloon. The service concludes with the hymn “Eternal Father, Strong to Save.” Services are simultaneously conducted in Second and Third Class as well, and many passengers of various religious denominations would have worshiped in their own ways at various times.

The Holland America liner Noordam has an ice warning forwarded to Titanic via the Caronia. The message began with the usual congratulations to Captain Smith and his ship before noting the weather experienced by the little single-stacker. It ended with a report of “much ice” at 42.24N to 42.45N and 49.50W to 50.20W. This message was acknowledged with a reply at 12:31pm.

The ship’s daily run is calculated and posted for what will be the last time. Since noon on the 13th, she has traveled 546 nautical miles and is located at 43.02N, 44.31W. During this period, she was steaming at 22.06 knots, her best speed yet. Passengers and crew alike begin discussing the possibility that the ship will reach New York on Tuesday night rather than her scheduled arrival on Wednesday morning. While not out to set any kind of speed record, Titanic was still being tested and her engines run-in. A full-speed run was planned for Monday, with the last of her 29 boilers being brought online Sunday in preparation for this action.

Hamburg-Amerika’s Amerika sends a message to Titanic with a request that it be forwarded to the Hydrographic Office in Washington, DC by the White Star liner with her more powerful transmitter. The message indicated “two large icebergs” at 41.27N, 50.8W. While this message was dutifully forwarded to the Cape Race wireless station at 9:32pm when Titanic was in range, there is no evidence that it made its way to her bridge officers or captain.

The White Star Line’s Baltic, the world’s largest ship when she entered service in 1904, sends a message to the current holder of that title that is full of news. Baltic reports that a Greek steamship, the Athenai, has reported “passing icebergs and large quantities of field ice” at 41.51N, 49.52 W. She also notes that there is a stranded German oil tanker, the Deutschland, that is out of coal at 40.42N, 55.11W and in need of a tow. This message places ice directly in the intended path of the oncoming Titanic. Captain Smith acknowledged the message at 2:57pm. It is this message that Smith passed to J. Bruce Ismay that afternoon, with Ismay pocketing the message and later showing it to some passengers. Ismay will later return the message a little after 7pm at Smith’s request so that the officers can plot it on their navigational chart.

Titanic makes her final major course adjustment, turning the “Corner” at position 42N, 47W. This would place her on a rhumb line course westerly toward the entrance to New York harbor and the Ambrose light ship, the official end point for a westward crossing. The confusion over Titanic’s subsequent position when disaster struck would lead to talk as to whether Smith elected to make this common maneuver later and thus take the ship further south to avoid ice. Investigation has concluded that Smith turned the corner on time and just a few miles southwest of the correct spot.

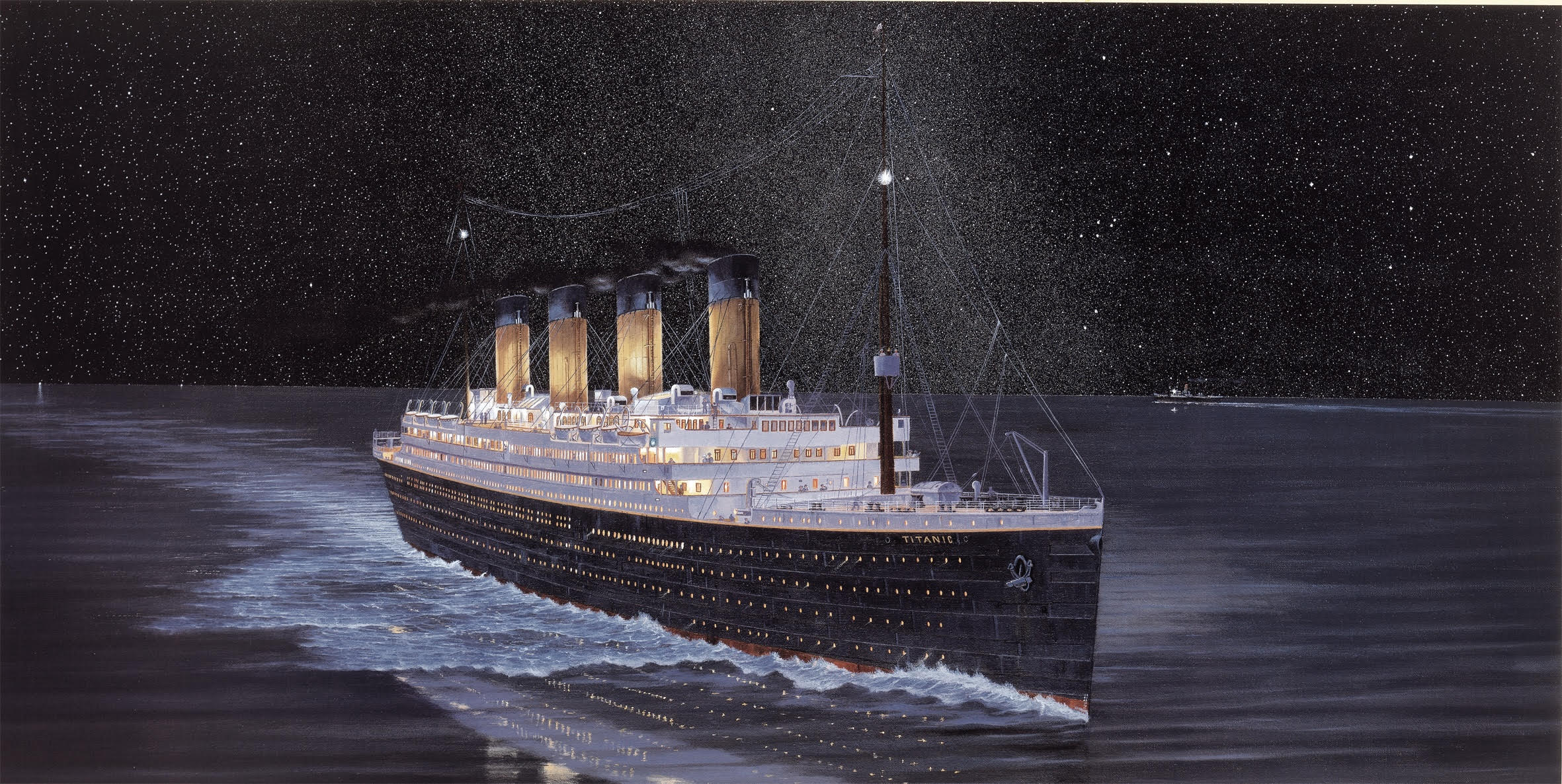

The ship witnesses a magnificent sunset, her last. A clear night arrives, the sea “like glass” according to Second Officer Charles Lightoller and a fantastic canopy of bright stars emerges as the light wanes and then disappears. There is no moon, and a day-long breeze gives way to complete calm. At the same time, the temperature, having dropped steadily all day, continues to plummet.

Image: Screenshot by Titanic Honour & Glory

The last dinner aboard Titanic is served in her various dining spaces. Captain Smith attends a party given in his honor in the ship’s restaurant later in the evening. At the same time, the last three of the ship’s 29 boilers are connected to the engines, increasing her revolutions and speed once more. Titanic is now under full power and working herself up to her full speed for the following day’s planned run.

First Officer William M. Murdoch, on duty temporarily while Lightoller, the officer of the watch, eats his dinner, orders Lamp Trimmer Samuel Hemming to close a forward hatch that is providing a glow. Murdoch notes that, as ice has been reported in the area, he wants no light ahead of the ship’s bridge so as to aid the efforts of her lookouts in the crow’s nest and on the bridge.

Captain Smith arrives on the bridge and converses briefly with Lightoller about the night and the ice that has been reported. Smith noted the falling temperature, now below 40 degrees and still falling, and the lack of wind. Lightoller remarked that it was “a flat calm.” Smith and Lightoller felt that, due to the clear conditions, ice would be spotted far enough away to take evasive action. As he made to leave, Smith said “if it becomes at all doubtful let me know at once” and then headed for his quarters just aft of the bridge on the starboard side.

Lightoller, thinking of the ice that the ship would likely encounter at some point during the night, has Sixth Officer Moody phone the crow’s nest on the liner’s foremast with the message “keep a sharp lookout for ice, particularly small ice and growlers” and the directive to inform subsequent watches the came up every two hours.

Artwork: The Last Sighting by Simon Fisher

The Mesaba of the Atlantic Transport Line sends the final warning of ice that Titanic would receive, noting “much heavy pack ice and great number large icebergs, also field ice” at 42N to 41.25N, 49W to 50.30W. Like the message from Baltic, this places ice directly in the path of the White Star liner, now traveling at just over 22 knots in the calm, clear night. There is no evidence that this important message ever reached Titanic’s bridge.

The last watch change before the collision occur, with Lightoller being replaced by Murdoch on the bridge and Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee taking over in the crow’s nest. Quartermaster Robert Hichens took the ship’s wheel. The ship is still making better than 22 knots as the new watch settles in. In the ship’s boiler rooms, the 8pm-12am watch is now half over as coal is fed continually into the liner’s hungry furnaces.

The wireless operator on the Californian, Cyril Evans, having been informed that they have stopped for the night after encountering an impassable ice field on their way toward Boston, calls up the Titanic, then the nearest ship to them, to warn of the ice they’ve come upon in the area and to report that they’re stopped until daylight. Evans assumes a chatty tone, beginning with “I say Old Man” rather than sending the warning as a Master Service Message that would’ve required Titanic’s operator to stand by, take down the message, and forward it to the bridge. The two ships’ close proximity causes Evans’ signals to nearly deafen Jack Phillips, then sitting at Titanic’s key with his headphones on as he vigorously worked the Cape Race station to send the many messages that had accumulated during the previous night and day. Phillips, frustrated by what seems an informal and unnecessary interruption, taps back “Shut up! Shut up! I am busy. I am working Cape Race!” Nonplussed by the brush-off, which is much less insulting in the vernacular of Marconi operators than it sounds to the unaccustomed observer, Evans listens to Phillips resumed traffic for a time before he switches his set off soon after and falls asleep reading.